Case Report

Mega colon Secondary to Chronic Constipation

Matthew Schultzel, Tom Arnold, Marcella Fornari, Maurizio Miglietta

Surgery, Palisades Medical Center, New Jersey, Edgewater, United States

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Constipation as a cause of mega-colon is rare. We describe a case of a 46 year old patient who developed mega-colon secondary to severe constipation. The patient had circulatory collapse secondary to cardiogenic shock and possibly intra-abdominal hypertension. The present (not a study) describes the diagnosis and treatment of mega-colon secondary to chronic constipation in a 46 year old patient. A CT scan revealed a massive dilated colon that was compressing the patient’s vena cava. Subsequently, the patient was in cardiogenic shock and suffered an MI. The patient exhibited symptoms of cardiogenic shock with pressures dropping to 64/48 requiring dopamine. An EKG demonstrated inferolateral ischemia, with TI initially 0.2, CK 79, and CKMB 1.7. The patient was admitted to the ICU. While in the ICU, the patient was intubated, sedated, and manually dis-impacted as he was unstable for operative intervention. Post procedure, a KUB was obtained showing less dilation of the colon and no free air. The physical exam was much improved and the patient was being weaned off pressure support. An echocardiogram was performed and demonstrated poor visibility of the left ventricle with an estimated ejection fraction of 60%. His cardiac enzymes were being trended resulting in TI of 0.89, CK 136, CKMB 10.9, Lactate 1.2, pH 7.14. Twelve hours later the patient suffered a massive MI, and expired with TI 11.2, CK 515, CKMB 59.3, and lactate 13.7.

Introduction

Constipation is subjectively defined by both the character and frequency of stool and it is one of the most common medical complaints [1]. A constipated stool is defined as a scyballous in which it has a dry, hard characteristic making is difficult to pass. Chronic constipation can be caused by a vast majority of disorders including but not limited to neurogenic disorders (Diabetes and Hirshprungs), non-neurogenic disorders (hypothyroid and pregnancy), and idiopathic disorders (decreased transit or dyssinergic defecation, drugs, and irritable syndrome)[1-3]. Two conditions to consider in the discussion of chronic constipation include fecal impaction and mega-colon. Fecal impaction is a large accumulation of hard stool, likely in the rectum, which is unable to be passed secondary to its large size and scyballous consistency. Mega-colon can be an extreme result of constipation which leads to a dilated, atonic colon [4]. It is infrequent that constipation causes mega-colon both in foreign and domestic literature. Our hospital recently reported the following case.

Case Report

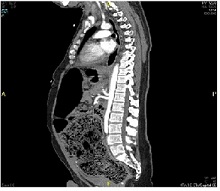

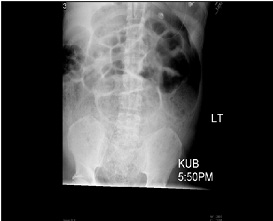

A 46 year old male with history of moderate mental retardation and previous bowel resection for constipation as a child presented to the emergency room with hypotension, diffuse abdominal pain, and complaints of constipation. He resided in a group home and could not communicate his last bowel movement. His cardiac enzymes were elevated with troponin level initially 0.2, creatine kinase 79, and creatine kinase -MB 1.7. He was hypotensive and diaphoretic and received pressure support with dopamine in the Emergency Department. The patient’s CT scan reviewed massively dilated loops of bowel, mega-colon, and a large amount of stool throughout the entire colon (Figure1, 2). No free air or pneumatosis noted. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, intubated, and sedated. A bladder pressure was not performed. He was gently manually dis-impacted resulting in a large amount of dry, hard stool being evacuated. A post-procedure KUB (Kidney Ureter Bladder X-Ray) was obtained approximately 2 hours afterwards showing much improved dilated colon and no free air (Figure 3). The patient had decreased vasopressor requirements and was slowly being weaned down, while his cardiac enzymes were being trended to troponin level 0.89, creatine kinase 136, creatine kinase -MB 10.9, Lactate 1.2, and pH 7.14. A soap suds enema was administered with a successful amount of stool returned. Serial abdominal exams every two hours revealed a resolution of his distension. Approximately twelve hours after his dis-impaction the patient suffered a massive MI with troponin level of 11.2, creatine kinase 515, creatine kinase -MB 59.3 and a lactate of 13.7. The patient subsequently expired.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Discussion

Chronic constipation is very common and often more difficult to remedy than an acute onset of constipation. Up to 17% of the U.S. population suffers from chronic constipation, with symptoms that can be difficult to recognize in certain populations and potentially refractory to common therapeutics. Constipation can be classified according to cause being primary or secondary [5]. Primary causes are considered those intrinsic to colonic motility and are generally considered after secondary causes are ruled out, and include: defecation disorders, pelvic floor dysfunction, slow transit constipation normal transit constipation and inflammatory bowel disease. Secondary causes include therapeutics, obstruction, metabolic disorders, neuropathies, systemic disorders, and psychiatric disorders.

Slow transit constipation is mostly seen in young females with infrequent bowel movements. This occurs from disordered colonic motor function around the time of puberty. In this group of patients conservative measures are usually unsuccessful. Conversely, patients with normal transit constipation generally have psychological stressors that cause them to have misperceptions of their bowel function [6].

Failure to empty the rectum completely is collectively known as defecation disorders. These are normally acquired in childhood but can remain asymptomatic due to the learned behavior to alleviate painful defecation. Defecation disorders are more common in the elderly due to excessive straining [6].

Disorders of the peripheral and central nervous system can lead to constipation due to impaired colonic and anorectal motor function. Sacral nerves carry the sympathetics that innervate the distal colon. Lesions in the cauda equina can cause colonic dilation and decrease rectal tone thus leading to constipation [1].

Intractable constipation, much like that experienced by our patient, has been associated with Hirschsprung’s disease especially in patients with mental retardation. Hirschsprung’s disease is defined as absence of ganglion cells in the colon and is found in 1.5% of Down Syndrome patients [7]. Most patients are diagnosed early after birth due to delayed passage of meconium. Late diagnosis is rare and most patients had presented previously to their primary physicians with distention, abdominal pain, and intractable constipation [7]. Delayed diagnosis is associated with more complicated surgical procedures such as the need for a stoma and development of enterocolitis. Enterocolitis in these patients presents as abdominal distention, fever, and sepsis and occurs in 21% of patients who were diagnosed and subsequently surgically managed late [7]. The death rate from Hirschsprung’s associated enterocolitis is 1% [7].

Chronic constipation typically falls into two categories: a disease of the young versus the old, both heavily dependent on lifestyle and usage of laxatives [4,8] . Although, much literature discusses constipation as a symptom of idiopathic or acquired mega-colon, it is a likely contributor to the development of the condition. A major cause of idiopathic chronic constipation is increased transit time also known as colonic inertia [1]. These patients lack an increase in motility after meals or in responsive to medical treatment. Outlet delay is another form of idiopathic constipation where patients have normal motility through the colon but stagnation in the rectum [1]. This is very commonly seen in Hirshprungs disease. The paucity of literature available on the progression of constipation to lethal mega-colon demonstrates its rare occurrence. However, patients with mental disorders may mask the presentation of symptoms and evolution of this condition. Extreme care should be taken with patients’ with an unknown evolution of such a condition.

Mega-colon is defined as colonic distention in the absence of obstruction. Acceptable diameter parameters of greater than 12cm in the cecum, 8cm in the ascending colon and 6.5cm in the sigmoid colon are most frequently used in the diagnosis. Mega-colon is commonly divided into three categories: acute, chronic (congenital, acquired, idiopathic) and toxic. This discussion focuses on chronic, non-congenital mega-colon. Causes of acquired mega-colon are frequently considered neurologic, metabolic or systemic diseases as well as pharmacologic causes. However, chronic constipation is thought to contribute to the development of mega-colon in children and there are reports of its role in adult pathophysiology.

There are no studies demonstrating the prevalence or incidence of mega-colon currently. The risk of perforation from non-toxic mega-colon is considered to be 3%.9 Other risks include abdominal compartment syndrome as well as compression of nearby structures, including the inferior vena cava. We did not measure intra-abdominal pressure in this case but his circulatory collapse could have been due to a component of intra-abdominal hypertension in addition to his MI.

Treatment in the absence of perforation includes evacuating the colon via dis-impaction, cathartics, laxatives, and beginning a bowel regimen. Subtotal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis should be considered in patients who are not responsive to medical treatment, have slow transit time, and do not have any other functional causes for the constipation such as pseudo-obstruction and pelvic floor obstruction [1].

Figure 3

Conclusion

Chronic constipation is a prevalent and insidious disease that can have significant sequelae including mega-colon. Mega-colon may lead to serious consequences, requiring prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment modalities. Mega-colon secondary to chronic constipation has not been well studied and further investigation can contribute to the recognition of this condition and potentially avoid increased morbidity and mortality associated with this condition. Additionally, it is unknown whether the pathology develops within the sigmoid and affects the colon proximally or if it is a different mechanism of colonic involvement. Further research in colonic motility would greatly expand this discussion.

Author’s Contribution

MS: Literature search and preparation of manuscript.

TA: Literature search and preparation of manuscript.

MF: Literature search and preparation of manuscript.

MM: Literature search and preparation of manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Ethical Consideration

Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Acknowledgement

None

Funding

None declared

Reference

[1].Wald, Arnold; Management of chronic constipation in adults; UpToDate May 7, 2013

[2].Yin H, Boyd T. Rectal biopsy in children with Down syndrome and chronic constipation: Hirschsprung disease vs non-hirschsprung disease.PediatrDevPathol. 2012 Mar-Apr;15(2):87-95. doi: 10.2350/11-01-0957-OA.1. Epub 2011 Oct 12.[pubmed]

[3].Khawaja MR, Akhavan N. Chronic constipation with megacolon. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Aug; 26(8):938. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1664-2. Epub 2011 Mar 1.[pubmed]

[4]Sparberg M. Constipation. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 89.[pubmed]

[5].Andrews, Christopher N., and Martin Storr, MD. "The Pathophysiology of Chronic Constipation." Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology 25 (2011): 16-21. [pubmed]

[6].Lembo, Anthony, Ullman, Sonal; Feldman: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 9th ed.; Chapter 18; pg 264-265

[7].Arshad, A, Powell, C, Tighe, MP. “Hirshprung’s Disease.” British Medical Journal. 2012 October; 345 (6): DOI: 10.1136/bmj.e5521. Epub 2012 October [pubmed]

[8].Huang ZC, Liu Q. Diagnosis and treatment of slow transit constipation complicated with adult megacolon, Zhonghua Wei Chang WaiKeZaZhi. 2011 Dec;14(12):941-3.[pubmed]

[9].Manual, David, MD, Michael Piper, MD, Roberto Gamarra, MD, and Clifford Ko, MS. "Chronic Megacolon." Medscape. Medscape, 11 July 2011. Web. 3 Jan. 2013