Case Report

Bile Duct Injury during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in a Polycystic Liver

Paolo Orsaria (1), Giuseppe Petrella(1), Oreste Buonomo (1), Maria Caputo(2), GiovanniSalvini(2), Marco Conte(2)

(1)Department of Surgery, Tor Vergata University Hospital, 00133 Rome, Italy

(2)Department of Surgery, San Giovanni Calibita Fatebenefratelli Hospital, 00187 Rome, Italy

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Introduction

Cystic lesions of the liver consist of a heterogeneous group of disorders and might present a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Large hepatic cysts are symptomatic and cause complications more often than smaller cysts. In addition, the anatomical localization might present an additional risk factor in the incidence of bile duct injury (BDI) during laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC).

Study design

Currently, there are no randomized trials concerning the increased incidence of BDI in patients with multicystic livers. To assess the specific diagnostic and management problems of this case the clinical benefits of early diagnosis, adequate surgical technique, and multidisciplinary management are discussed.

Material and methods

We described a case of bile duct injury following LC in a patient with a preoperative diagnosis of multicystic liver and cholelithiasis, analyzing the disease treatment profile through findings on physical examination, laboratory, radiological and pathological investigations.

Results

The intraoperative detection of bile leakage facilitated the immediate repair of the biliary tree with a good surgical and clinical outcome at 18 months follow-up.

Conclusions

The manifestation of bile duct injuries during the postoperative period might be reduced through early detection and timely management. Improved results can be achieved through the judicious selection of a combination of interventions in the majority of patients. These diagnostic and therapeutic topics might offer a new classification system with economic and functional value to improve the performance and surgical outcome of the patient.

Key Words

multicystic liver, bile duct injury, BDI, cholelithiasis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Introduction

The observation of simple hepatic cysts, previously considered rare, is now relatively common in adults, affecting 3% to 7% of patients older than 70 years. Only 15-16% of these cysts are symptomatic, generating symptoms due to the size and anatomical location of the cyst, or the advent of complications, such as rupture, infection, or compression of the biliary system [1]. Moreover, hepatic cysts might present a problem during laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), particularly when localized in segment IV. Currently, there are no randomized trials concerning the increased incidence of bile duct injuries (BDI) in patients with multicystic livers. In this context, the rate of BDI is slightly higher with laparoscopic surgery than with open surgery (0.5% and 0.15%, respectively) and anatomic variants of the biliary tree alone constitute one of the major groups of risk factors [2]. Only 25%-32.4% of injuries are recognized during LC, which is considered the best procedure for repair [3]. Immediate reconstruction minimizes the associated morbidity and there is accumulating evidence to support the importance of early referral to a tertiary care hospital, which provides a multidisciplinary approach. In this report, we present a case of a BDI following laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a patient with a preoperative diagnosis of multicystic liver and cholelithiasis. The specific diagnostic and management problems of this case are presented, and the disease treatment is discussed.

Case Report

A 62-year-old male, affected with symptomatic cholelithiasis for more than 1 year, was admitted to our hospital to undergo LC. The patient reported a progressing history of abdominal discomfort, nausea, bloating and weight loss. Laboratory investigations revealed a normal hematocrit, hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, and platelet number. The liver function tests did not show obstructive jaundice, with a total bilirubin of 1.2 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 110 u/L and GPT 23 u/L. The hepatitis serology was negative. A 3.6-cm cyst was observed in the hilum, softly marking vascular and bile structures, and other cysts in the left lobe of up to 2.7 cm, without biliary tree dilatation, were identified in the liver. Furthermore ultrasonography detected the presence of biliary sludge and gallstones in the gallbladder. LC was performed. During abdominal exploration, a large thick-walled cyst (>5 cm) extending from segment IV and compressing the confluence of hepatic ducts and gallbladder was revealed, and a second cyst of approximately 3 cm at the level of segment III was observed behind the cranial portion of hepatoduodenal ligament.

The dissection of Calot’s triangle was difficult due to fatty tissue inflammation and cyst location. We performed an antegrade dissection using ultrasonic-activated coagulating shears until reaching the segment IV cyst. Moreover, the gallbladder dissection was complex due to the medial and anterior displacement of the vascular and biliary tract.

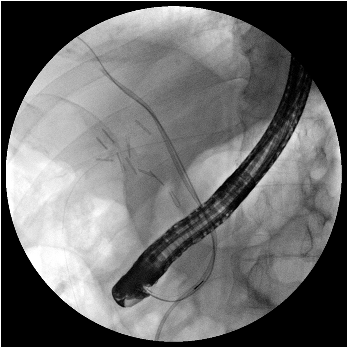

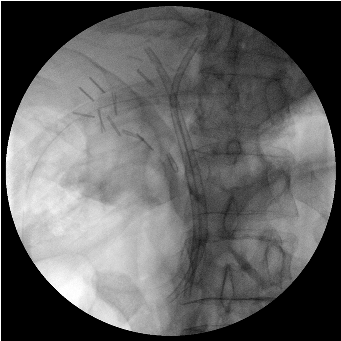

Before dividing any structure, we performed laparoscopic fenestration and, after the serous cyst deroofing, a histological examination of multiple specimens from the cystic wall was conducted. The intraoperative frozen sections showed no evidence of malignancy, while the cytology and cultures of the cystic fluid were negative. Immediately after the gallbladder was released from the liver bed, we separated both the hanging cystic duct and the cystic artery, displaced anteriorly and medially from the right hepatic artery. LC was performed after clipping of the structures with titanium clips. We fenestrated the segment III cyst, and filled it with serum. In the control phase, we improved hemostasis due to diffuse bleeding from the gallbladder bed. We also identified slight biliary spillage from the bottom edge to the residue IV segment cyst marsupialization, followed by the application of two titanium clips. Upon further review, after application of the white hemostatic matrix, we detected additional bile spreading from the proximal portion of the bile duct. After careful washing and renewed control of the ligatures, we conducted laparoscopic magnification imaging to inspect the hepatic pedicle, revealing a small lesion in the postero-lateral wall of the common bile duct. To investigate the anatomic pattern of the injury, we removed the clip on the cystic duct and performed intra-operative cholangiography. The results showed a contrast spreading near the hepatic confluence. The surgical procedure was converted to laparotomy, and after biliary tract preparation, we observed a lesion on the postero-lateral wall of the common hepatic duct near the confluence, potentially reflecting an ectopic cyst bile duct injury. Subsequently, the distal end of a 5-mm gauge ureteral catheter was inserted through the papilla into duodenum and controlled through X-ray examination; subsequently, the lesion was sheltered. Biliary reconstruction was performed using transverse polyglactin sutures (Vicryl 5/0®). No bile spillage was observed and a subhepatic drainage was placed. During the second postoperative day, no abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting or fever was recorded, and the patient was referred to a specialized hepatobiliary unit. The patient was subjected to endoscopic sphinterectomy and double internal stenting, followed by the resolution of the clinical and radiological status (Figure 1-2).

Figure 1. Endoscopic treatment through sphinterectomy and double internal stenting. The guide wire is passed from common bile duct to right lobar duct, followed by the insertion of a 5-mm gauge ureteral catheter tutor, inserted through the papilla into duodenum during the previous intraoperative lesion repair.

After one month, the follow-up exam revealed no obvious abnormalities in the liver function test and the double stenting was removed. At the six-month follow-up exam, the laboratory investigation revealed normal values for the hematocrit, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, ALP, ALT, AST, and total and direct bilirubin, with no biliary manifestation of post-cholecystectomy syndrome. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed to exclude hilar and subhepatic collection, biliary leaks or strictured ducts, which showed no evidence of biliar abnormalities in this shortrange time.

Figure 2. Endoscopic treatment through sphinterectomy and double internal stenting combined with the resolution of the clinical and radiological status. The successful completion of stent placement (second stent was inserted through the common bile duct into the left hepatic duct), controlled through X-ray examination.

Discussion

The pathogenesis and correlation between cholelithiasis and multicystic liver is not clear. The development and the frequent use of US and CT scanning led to an increased detection of simple hepatic cysts, which give rise to a new therapeutic challenge. The larger entities cause not only symptomatic complications, but also an additional risk factor in the BDI pattern, as observed in the present case study. The management of simple hepatic cysts includes different treatment options, such as percutaneous procedures and sclerotherapy, internal drainage with cysto-jejunostomy, hepatic resection and liver transplantation. Laparoscopic fenestration represents the best risk benefit ratio in terms of the recurrence rate and surgical invasiveness. Percutaneous (US- or CT-guided) needle aspiration has been associated with high relapse rates (approximately 80% to 100%), which are reduced approximately 20% when combined with alcohol minocycline chloride or tetracycline chloride injections [4]. Internal drainage through cysto-jejunostomy or hepatic resection with fenestration is a valuable option for patients with symptomatic and more severe parenchymal involvement; however, previous studies have reported morbidity rates from 20% to 100% and mortality rate between 3% and 10%, which are higher values than those observed with laparoscopic fenestration, with 30% and 1%, respectively [5]. The laparoscopic deroofing of liver cysts is a safe and functional treatment, with a 9% average recurrence rate and 4.5% symptomatic resubmission. Moreover, this treatment can be performed in 94% of reported cases, with 90% clinical benefit in patients undergoing this procedure [6].

Other laparoscopic surgical techniques, including the gallbladder antegrade dissection (GAD), are often used in difficult cholecystectomies with acute inflammation, fibrosis, Calot’s triangle and cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Some reports show a significant reduction in the conversion of laparoscopic cholecystectomies (1.2% to 2% vs. 5.2% to 18.75%), a faster surgical time (70 vs. 90 min) and an equal incidence of common bile-duct residual choledocholithiasis (1.6% vs. 1.7%) in patients treated with GAD compared with subjected to conventional laparoscopic procedures [7]. The antegrade dissection technique is not aimed to lower the conversion rate in difficult cases, but should be evaluated in randomized multicenter trials to define the specific indications and advantages of ultrasonically activated scalpel options. The perspective of closing both the structures with shears makes the technique even more attractive but should be studied further. While some reports showed that the cystic artery is adequately closed using an ultrasonic technique, future large-scale clinical experiences should assess similar safety and versatility in cystic ducts. Cystic duct and artery occlusion using titanium clips, followed by section through ultracision is typically used when we practice anterograde cholecystectomy.

A potential disadvantage of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the risk of bleeding from the gallbladder bed, when using the ultrasonic shears. Dissection using an ultrasonic scalpel is facilitated through a thickened gallbladder bed, but when there is no inflammation, the gallbladder is thin making liver tissue injury with bleeding a potential risk.

Another mechanism of injury during LC is the lateral spread of electrical energy when using electrocautery, particularly if long contact times and delivery are employed. The ultrasonic dissection energy is typically focused on the tissue inside the shears, with only minimal lateral spreading; however, no comparative studies have yet shown whether the injuries caused through electrocautery would be avoided using the “laparosonic dome down” procedure.

In experienced centers, most of the major BDI is detected and managed during cholecystectomy Adequate results are achieved through the judicious selection of a combination of interventions in most patients. Because BDI occurs in a wide spectrum of clinical settings, experienced hepatobiliary surgeons, therapeutic endoscopists and interventional radiologists are important components to execute the multidisciplinary management, which might be warranted in a significant proportion of patients. Unfortunately, late diagnosis, multiple repair attempts and neglected medical care result in the extension and increased complexity of bile duct repair.

A retrospective literature review revealed several bile duct injury classifications, but none are universally accepted, as each has category has clinical and prognostic limitations. The data from Institutional Experiences shows different correlations with the final outcome after surgical repair (Bismuth), major and minor ductal lacerations or transections (McMahon) and the stratification of laparoscopic extra-hepatic injuries (Strasberg), but none of the proposed classifications considers the clinical condition of the patient, the time of recognition and the presence of sepsis to define the optimal management.

The architectural and anatomical limitations of iatrogenic lesions described in the era of the open surgery should be reassessed and integrated, as biliary tract injuries increase from 0.1%-0.2% in the open cholecystectomy era to 0.4-0.7% in the laparoscopic procedure era [8]

The best results were achieved when the BDI is recognized and repaired during the index operation, but nationwide surveys reported an intraoperative detection rate of less than 50% (9). Given its high prognostic value (i.e., high resolution imaging through a laparoscopic camera, cholangiography to define the nature of injury, and hemostatic arrays to counteract the biliary spillage), intraoperative suspicion should be followed by the prompt execution of technical measures for improving this diagnostic stage. In a retrospective analysis of 5.782 cholecystectomies performed between 1989 and 2007 revealed a BDI incidence of 1%, and the intraoperative detection occurred in 43% of the patients using LC compared with only 10% during open surgery. The mortality rate in this study was 9% (5/57 patients) in the group of patients with a late diagnosis of lesion (63% was detected after operation). In this series, all patients undergoing management during the same operation showed excellent or good results. The endoscopic treatment through sphinterectomy and drainage through the insertion of an internal biliary stent was effective in 80%-100% of patients with bile leaks, ensuring better and long-lasting therapeutic success (10). In addition to reducing intraductal pressure, the biliary stent also covers the leakage point, facilitating healing. Bile leaks from the cystic duct stump or small ducts in the liver bed have been more commonly reported after laparoscopic cholecystectomy than with open cholecystectomy, and bile leaks usually result from an injury to the minor duct that remains in continuity with the common bile duct.

Conclusions

Further clinical trials are needed to validate endoscopic therapy as a treatment option, thus limiting the surgical procedures for patients experiencing the complete sectioning of the bile duct, the failure of previous surgical repairs or the failure of endoscopic treatment. To assess the clinical impact of the surgical technique used in this study as a new treatment proposal, to reduce complications of external biliary fistula, further efforts should quantify the clinical benefits of early diagnosis, adequate surgical technique, with complete laparoscopic bile duct repair, and multidisciplinary management in experienced hepatobiliary centers. These diagnostic and therapeutic topics might offer a new classification system with economic and functional value to improve the performance and surgical outcome of the patient.

Learning Points

Currently, there are no randomized trials concerning the increased incidence of bile duct injuries (BDI) in patients with multicystic livers.

The manifestation of BDI after laparoscopic cholecystectomy might be reduced through early detection and timely management.

Immediate reconstruction and multidisciplinary approach could minimize the associated morbidity.

These diagnostic and therapeutic topics might offer a new classification system with economic and functional value to improve the performance and surgical outcome of the patient.

Conflict of Interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical Considerations

The written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Authors Contributions

PO, GP, OCB carried out the literature search, prepared the case report and conclusions draft, and edited the final manuscript.

MC, CS, MC prepared the literature review and discussion draft, and edited the final manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding

None

References

[1]Everson GT, Taylor MR, Doctor RB. Polycystic disease of the liver. Hepatology 2004; 40:774-82.[pubmed][pubmed]

[2]Coakley FV, Schwartz LH, Blumgart LH, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, Panicek DM. Complex postcholecystectomy biliary disorders: preliminary experience with evaluation by means of breath-hold MR cholangiography. Radiology 1998;209:141-6.[pubmed]

[3]. Archer SB, Brown DW, Smith CD, Branum GD, Hunter JG. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a national survey. Ann. Surg. 2001; 234: 549–58.[pubmed]

[4]. Garcea G, Pattenden CJ, Stephenson J, Dennison AR, Berry DP: Nine-year single-center experience with non-parasitc liver cysts: diagnosis and management. Dig Dis Sci 2007, 52:185-191.[pubmed]

[5].Russel RT, Pinson CW. Surgical management of polycystic liver disease. World Gastroenterolgy 2007; 13(38): 5052-5059.[pubmed]

[6]Fabiani P, Iannelli A, Chevallier P, Benchimol D, Bourgeon A, Gugenheim J. Long-term outcome after laparoscopic fenestration of symptomatic simple cysts of the liver. Br J Surg 2005; 92:596-7.[pubmed]

[7]Gupta A, Agarwal PN, Kant R, Malik V. Evaluation of fundus first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2004;8:255–258.[pubmed]

[8]Lai EC, Lau WY. Mirizzi syndrome: history, present and future development. ANZ J Surg 2006; 76: 251–7.[pubmed]

[9]. Gigot J, Etienne J, Aerts R, Wibin E, Dallemagne B, Deweer F et al. The dramatic reality of biliary tract injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an anonymous multicenter Belgian survey of 65 patients. Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 1171–1178.[pubmed]

[10]Eisenstein S, Greenstein AJ, Kim U, Divino CM. Cystic duct stump leaks: after the learning curve. Arch. Surg. 2008; 143: 1178–83.[pubmed]