Research

Fine needle aspiration versus core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of the intraductal breast papillary lesions

Yoko Omi, Tomoko Yamamoto, Takahiro Okamoto, Toshio Nishikawa and Noriyuki Shibata

Departments of Pathology, Endocrine Surgery and Surgical Pathology, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, 8-1 Kawada-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8666, Japan

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background

Diagnosing breast intraductal papillary lesions by fine needle aspiration (FNA) is often difficult and provides indeterminate results. The aim of this study was to determine an effective diagnostic method for intraductal papillary lesions, when the initial FNA cytology was insufficient.

Patients and Methods

The cytopathology records of 79 women diagnosed with intraductal papillary lesions were retrospectively evaluated

Results

Of the initial FNAs, 26 specimens were classified as benign, 51 were indeterminate, and 2 were suspicious for malignancy. Repeat FNAs or core needle biopsies (CNBs) were performed on 20 and 23 cases, respectively. Thirteen of 20 cases (65%) of the second FNA specimens and 6 of 23 cases (26%) of the CNBs were indeterminate. The probability of indeterminate diagnosis was significantly lower in the CNBs than the second FNAs (p<0.05). However, some cases failed to be diagnosed by CNB, partly because the samples were insufficient for diagnosis, and partly because the lesions seemed to be beyond the diagnostic capability of CNB even with an aide of immunohistochemistry using multiple primary antibodies. Overall, 13 of 79 cases were malignant. /p>

Conclusions

For intraductal papillary lesions initially diagnosed using FNA, a CNB may be recommended instead of FNA, if additional evaluation is required. An adequate CNB may facilitate accurate diagnosis, although some cases will remain indeterminate.

Key words

Intraductal papillary lesion, Fine needle aspiration, Core needle biopsy

Introduction

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is a simple and minimally invasive procedure that provides cytological specimens to diagnose breast lesions. Patients desire a fast, reliable, and minimally invasive examination. However, intraductal papillary lesions including ductal hyperplasia, intradutal papilloma and ductal carcinoma in situ have cytologic features that are difficult to differentiate as benign or malignant. Although some studies have found that there was no difference between the diagnostic accuracy of FNA and core needle biopsy (CNB) for papillary lesions [1, 2], others have reported the diagnostic accuracy of FNA ranging from 27% to 88% [3-5]. CNB is a useful diagnostic tool for breast lesions, and can also be performed as an outpatient procedure. It is more traumatic to patients than FNA, but the larger specimen can be more informative, especially regarding structural evaluations. CNBs allow assessments of invasiveness and grade, and immunohistochemistry using multiple primary antibodies can be performed. If the result of an FNA is an indeterminate papillary lesion, what procedure should the physician subsequently perform to obtain a definitive diagnosis? This retrospective study compared the results of subsequent FNAs versus subsequent CNBs for intraductal papillary breast lesions initially diagnosed by FNA.

Patients and methods

The cytopathology records of 79 women, diagnosed as intraductal papillary lesions using FNA during a 4-year period between 2006 and 2009 at the Department of Endocrine Surgery, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, were retrospectively evaluated. The mean age of the patients was 45.5 years (range, 25-76 years). The mean diameter of the lesions was 1.4 cm (range, 0.4-3.5 cm). Surgeons performed FNA under ultrasound guidance using 23- or 22-gauge needles. The sample aspirates were smeared on a slide, fixed with 95% ethanol, and stained using Papanicolaou stain. Cytological feature showing clusters of papillary growing epithelial cells with foamy cells in the background was considered to be an intraductal papillary lesion. FNA results were reported as normal or benign, indeterminate, suspicious for malignancy, or malignant, according to the guidelines published by the Japanese Breast Cancer Society [6]. Estimated histology was also mentioned. For cytopathological diagnosis, cytotechnologists evaluated the quality of specimens and screened out the normal or benign ones. Specimens considered to be indeterminate, suspicious for malignancy, or malignant were then examined by cytopathologists. Cases that were determined to be malignant by initial FNA were excluded in this study. For additional examinations including the second and third examinations, FNAs, or CNBs or excisional biopsies were performed. CNBs were performed under ultrasound guidance by surgeons using 16-gauge spring-loaded biopsy guns. At least 2 cores were taken for each lesion. Pathologists performed the histological diagnosis. An intraductal papillary lesion was defined as intraductal epithelial proliferations supported fibrovascular stalks with or without an intervening myoepithelial cells [7]. Immunohistochemistry was performed as needed. For myoepithelial markers, primary antibodies against smooth muscle myosin (clone SMMS-1, 1:100; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), smooth muscle actin (clone 1A4, 1:100; Dako), calponin (clone CALP, 1:100; Dako) and p63 (clone 4A4, 1:50, Dako) were used. For high-molecular-weight keratins (HMWKs), antibodies against CK5/6 (clone D5/16B4, 1:50; Dako) and CK34bE12 (clone 34SSe12, 1:100; Dako) were used. For neuroendocrine markers, antibodies against synaptophysin (clone SY38, 1:100; Dako) and chromogranin A (clone M869, 1:100; Dako) were used. Antibody binding was visualized using the polymer immunocomplex method (Envision System; Dako), with 3,30-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) as the chromogen and hematoxylin as the counterstain. For statistical analysis, the Excel® Statistical Program File ystat2004.xls (Igaku Tosho, Tokyo, Japan) was used. The rate of indeterminate results between the second FNAs and the CNBs was compared by Fisher’s exact probability test. Statistical significance was defined as P values less than 0.05. Moreover, the initial FNAs were reevaluated by two cytopathologists (Y.O. and T.Y) without any clinical information, to verify reproducibility on the diagnosis of initial FNA. Cases were reviewed randomly to avoid knowing the information of initial diagnosis. Chi-square test was performed.

Results

Probability of indeterminate diagnosis on the second FNA and CNB

Detailed results are summarized in Table 1

Table 1. Summary of indeterminate cases on the second examinations and of overall malignant cases

|

Results of

initial FNA

|

Indeterminant

cases

|

Overall

malignant

|

|

Second FNA cases

|

Second CNB cases*

|

P value

|

|

Benign

|

1/2 (50%)

|

1/1 (100%)

|

NS

|

1/26 (4%)

|

|

Intermediate

|

11/17 (64%)

|

4/21 (19%)

|

0.01

|

11/51 (22%)

|

|

Suspicious for

malignancy

|

1/1 (100%)

|

1/1 (100%)

|

NS

|

1/2 (50%)

|

|

Total

|

13/20 (65%)

|

6/23 (26%)

|

0.024

|

13/79 (16%)

|

FNA- Fine needle aspiration; CNB - core needle biopsy; NS- not significant

*Cases of inadequate specimen are included

Of the 79 papillary lesions, 26 were benign, 51 were indeterminate, and 2 were suspicious for malignancy. Among 26 cases classified as benign, a subsequent FNA was performed for 2 cases, CNB for 1, and excisional biopsy for 2. One of 2 (50%) second FNAs were indeterminate. A definitive diagnosis could not be made for the 1 CNB (100%) because the specimen was inadequate for diagnosis. There was no significant difference between the rate of indeterminate result of repeat FNAs and CNBs. A total of one of 26 cases (4%) that were found to be benign by the initial FNA ultimately proved to be malignant. Among 51 cases classified as indeterminate, a subsequent FNA was performed for 17, CNB for 21, and excisional biopsy for 2. Eleven of 17 lesions (64%) undergoing a second FNA were still indeterminate. A definitive diagnosis was not possible in 4 of 21 (19%) lesions undergoing CNB; 3 were indeterminate, and another one was inadequate for diagnosis. The rate of indeterminate result was significantly lower when the second examination was performed by CNBs than repeat FNAs (p<0.05). A total of 11 of 51 cases (22%) that were indeterminate after the initial FNA were ultimately diagnosed as malignant./p>

Among 2 cases classified as suspicious for malignancy, FNA was performed for 1 and CNB for 1. Both the second FNA and CNB were indeterminate. There was no significant difference between the rate of indeterminate result of repeat FNA and CNB. A total of 1of 2 cases (50%) with results suspicious for malignancy after the initial FNA were ultimately diagnosed as malignant.

Repeat FNAs or CNBs were performed on a total of 20 and 23 cases, respectively, and 65% (13/20) of the second FNA specimens and 26% (6/23) of the CNBs were indeterminate. The probability of indeterminate diagnosis was significantly lower when the second examination was performed by CNBs than repeat FNAs (p<0.05). Overall, 13 of 79 cases (16%) were malignant. According to the reevaluation of the 79 papillary lesions, 33 were benign, 44 were indeterminate, and 2 were suspicious for malignancy. There was no significant discordance before and after the reevaluation. It confirmed that the diagnosis of initial FNA was reproducible./p>

Additional examinations after the second examinations

Additional examinations were performed on 15 of 19 cases that were nondiagnostic by the second FNA or CNB (Table 2). FNAs, CNBs, or excisional biopsies were performed on 11 cases indeterminate by the second FNA.

Table 2. Summary of additional examinations for final diagnosis, after the second fine-needle aspiration and core needle biopsy

|

Second

Examination

|

|

Additional

Examination

|

|

Methods

|

Category

|

Cases

|

Method

|

Malignant total

|

|

FNA

|

Indeterminant

|

13

|

FNA

|

0

|

|

CNB

|

1/4

|

|

Excision biopsy

|

3/5

|

|

No examination

|

ND/2

|

|

CNB

|

Indeterminant

|

3

|

Excision biopsy

|

1/1

|

|

No examination

|

ND/2

|

|

Inadequate

|

3

|

FNA

|

0/1

|

|

Excision biopsy

|

2/2

|

FNA - Fine needle aspiration; CNB- core needle biopsy; ND- Not determined

Representative cytology and histology of indeterminate lesions

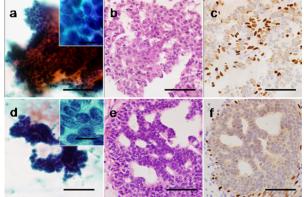

Representative cytology and histology of lesions that were diagnosed to be indeterminate on the initial FNA are presented in Figure 2. Figure 2 illustrate 2 cases that proved to be benign (Figures 1a-c) or malignant (Figures 1d-f) on subsequent CNBs. For these cases, the ductal cells exhibited a papillary growth pattern, and myoepithelial cells could not be clearly visualized on FNA specimens (Figures 1aand 1d). In the benign case, CNB tissue sections exhibited heterogenous cell growth, and immunohistochemistry of myoepithelial markers such as p63 supported a benign diagnosis (Figures 1b and 1c).

Figure 1: Representative microphotographs of breast papillary lesions that were initially diagnosed to be indeterminate by fine needle aspiration (FNA), and subsequently diagnosed as benign by core needle biopsy (CNB) (a-c) or as malignant by CNB (d-f). FNA aspirate (a, d), CNB tissue sections (H & E) (b, e), and immunostaining for p63 (c, f). In both cases, myoepithelial cells are not clearly visualized among the papillary growth pattern on cytology specimens (a, d). The benign case shows a pattern of heterogenous cell growth (b) with myoepithelial cells confirmed by p63 immunostaining (c). Cancer cells grow in cribriform and partially solid patterns (e), and myoepithelial cells are absent within the nests of malignant-appearing cells (f). Bars = 100 mm, Bars for insets = 20 µm.

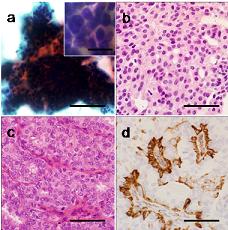

By contrast, on CNB tissue sections of the malignant case, cancer cells grew in cribriform and partially solid patterns with an absence of myoepithelial cells (Figures 1e and 1f). HMWK-positive cells exhibited a mosaic pattern in benign lesions, which were also negative for expression of neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin or chromogranin A. There were 3 cases where the results of the second CNB yielded an indeterminate papillary lesion, all of them were diagnosed as indeterminate on initial FNA. The cytological appearance indicated that they were likely to be benign, showing mild cellular atypia, but they showed papillary or solid growth patterns with unclear myoepithelia, particularly in the cases where the initial FNA diagnosis had been indeterminate. The histology presented atypical cribiform-like structures. There were only a few or no cells positive for myoepithelial markers within an intraductal growing component. Immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers was performed for one of the 4 cases, with negative results. Figure 2 is an example of a lesion that was indeterminate on the initial FNA (Figure 2a), thought to be an indeterminate papillary lesion on the CNB (Figure 2b), and proved to be ductal hyperplasia on an excisional biopsy (Figure 2c and 2d). Although cells positive for myoepithelial markers were seen on the excisional biopsy (Figure 2d), the rather monotonous, solid, and cribiform-like structures seen on the CNB suggested a possibility of malignancy (Figure 2b).

Figure 2: Representative microphotographs of a breast papillary lesion that was diagnosed to be indeterminate by both FNA and CNB. FNA aspirate (a), CNB tissue section (H & E) (b), tissue section of excisional biopsy specimen (H & E) (c) with immunostaining of smooth muscle myosin (d). Myoepithelial cells were not clearly visualized among the papillary growth pattern on cytology (a). Ductal cells show mild atypia and solid or cribriform-like structures (b, c). Myoepithelial cells are seen (d). Bars = 100 µm, Bars for insets = 20 µm.

Discussion

The advantages of FNA are 1) suitable for lesions located in areas difficult to access or in superficial sites, 2) easy and quick to perform [8], and 3) less invasive for patients because of the use of narrow-gauge needles. Breast lesions located near the skin or in deep areas, lesions containing fluid, and small lesions are good indications for FNA. However, a precise diagnosis is sometimes not easy to obtain with FNA, especially for intraductal papillary lesions, because there are difficulties in evaluating structural atypia and performing immunocytochemistry employing multiple primary antibodies. CNB is attractive because it can provide a larger specimen, thereby decreasing the rates of inadequate or suspicious results [8]. Immunohistochemistry performed on tissue sections of a CNB specimen can facilitate the diagnosis of papillary breast lesions [9]. The use of CNB for breast lesions has been increasing [10, 11]. Studies have reported that CNB has high accuracy [12, 13], although up to 35% of the benign papillomas diagnosed from CNB specimens were upgraded to either atypical or malignant on subsequent examination [2, 14-16]. Intraductal papillary lesions of the breast are difficult to diagnose and are frequently categorized as indeterminate on FNA cytology. Several studies [4, 5, 17, 18], but not all [1], have shown that most papillary lesions can be diagnosed by FNA. The diagnostic accuracies of FNA and CNB for breast lesions have been compared in several studies [2, 11, 19-21]. Some found that there was no difference [1, 2], but others recommended CNB over FNA [11, 19, 21]. Accuracy may depend on the size of the lesion [20]. Hukkinen et al. [22] reported that FNA requires more additional needle biopsies than CNB. Because an unsuccessful preoperative biopsy results in extra cost and delay in surgical treatment, they recommended that CNB should be performed as the initial biopsy. The findings of our study, showing the significantly higher diagnostic accuracy on CNBs as a method for the second examination, support this conclusion. There were a few discordant cases before and after the reevaluation of initial FNA. This discordance is probably due to the manner of reevaluation that was only based on cellular features without any clinical information. This may also suggest the difficulties on the diagnosis of intraductal papillary lesions only by cytological features.

Six of 23 (26%) second CNB specimens were indeterminate in our study, which included 3 specimens inadequate for diagnosis. In 2 cases, the diameters of the lesions were less than 1 cm. The lesion of the third specimen was 2.4 cm in diameter, but the sample was damaged. Small targets are more difficult to hit by core needles than by fine needles. However, the quality of the sample may improve if the biopsy technique is improved. A relatively large lesion may be a good indication for stereotactic biopsy. If the lesion is too small for stereotactic biopsy, excisional biopsy can be recommended. It should be noted that some papillary lesions are hard to diagnose even by using CNB facilitated by immunohistochemistry; this includes papillary lesions with minimal or mild cellular atypia that show solid or cribriform-like structures with indistinct myoepithelial cells. Such lesions are considered to be beyond the diagnostic capability of CNB, to say nothing of FNA. This difficulty is reflected by our findings that 22% of the lesions initially classified as indeterminate were ultimately diagnosed as malignant.

Thus, CNB is not always perfect, but the lower rate of indeterminate results provided by CNB over FNA may allow earlier and more accurate diagnoses of intraductal papillary lesions. An indeterminate result and repeated examinations may interfere with the doctor-patient relationship; therefore, physicians should do their utmost to obtain the final diagnosis as quickly as possible. For achieving this, if the initial FNA is not diagnostic, CNB is considered to be suitable for the second procedure. Moreover, if intraductal papillary lesions are clinically highly suspected before biopsy, CNB appears to be preferable over FNA for the initial evaluation.

Conclusion

If an initial FNA reveals a lesion to be papillary, and further examinations are required, the subsequent procedure should be CNB instead of FNA. Examiners should do their best to obtain a CNB specimen sufficient for a definitive diagnosis, although there will be some cases that are indeterminate, even on CNB.

Abbreviations

FNA: Fine needle aspiration biopsy; CNB: Core needle biopsy; High-molecular-weight keratin: HMWK; 3,30-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride: DAB; Magnetic resonance imaging: MRI;

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict interests.

Authors' Contribution

YO carried out study design, clinical studies, cytological and histological review, data analysis and manuscript preparation. TY carried out: study design, cytological and histological studies and manuscript review. TO carried out clinical studies and manuscript review. TN carried out histological studies and manuscript review. NS carried out histological studies and manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank Ms. M. Saito, Ms. T. Kanamuro, Mr. Y. Nonami, Mr. S. Takahashi, Ms. A. Konakawa, Mr. M. Sakurada, Mr. Y. Hasegawa, Mr. N. Sekine and Mr. T. Ito, of the Department of Surgical Pathology for their excellent technical assistance.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report

Funding

None

References

[1].Masood S, Loya A, Khalbuss W. Is core needle biopsy superior to fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of papillary breast lesions? Diagn Cytopathol. 2003 Jun;28(6):329-34.Pub MedPMID:12768640 [pubmed]

[2].Valdes EK, Tartter PI, Genelus-Dominique E, Guilbaud DA, Rosenbaum-Smith S, Estrabrook A. Significance of papillary lesions at percutaneous breast biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 Apr;13(4):480-2. PubMed PMID: 16474908.[pubmed]]

[3].Tse GM, Ma TK, Lui PC, Ng DC, Yu AM, Vong JS, Niu Y, Chaiwun B, Lam WW, Tan PH: Fine needle aspiration cytology of papillary lesions of the breast: how accurate is the diagnosis? J Clin Pathol. 2008 Aug; 61(8):945-9. PubMed PMID: 18552172 [pubmed]

4]. Michael CW, Buschmann B: Can true papillary breast lesions of the breast and their mimickers be accurately classified by cytology? Cancer. 2002 Apr 25; 96(2):92-100. PubMed PMID: 11954026

[pubmed]

[5]. Field a, Mak A: A prospective study of the diagnostic accuracy of cytological criteria in the FNAB diagnosis of the breast papillomas. Cancer. 2002 Apr 25;96(2):92-100. PubMed PMID: 11954026 [pubmed]

[6].The Japanese Breast Cancer Society: General rules for clinical and pathological recording of breast cancer. 16th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara-shuppan, 2008: 65-66. Japanese

[7]. Tavassoli FA, Hoefler H, Rosai J, Holland R, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, Boecker W, Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Moinfar F, Lakhani SR: Intraductal proliferative lesions.. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology Genetics Tumours of the breast and female genital organs Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. p. 63-73.

[8]. Tse GM, Tan PH: Diagnosing breast lesions by fine needle aspiration cytology or core biopsy: which is better? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 Aug;123(1):1-8. PubMed PMID: 20526738 [pubmed]

[9].Tse GM, Tan PH, Lacambra MD, Jara-Lazaro AR, Chan SK, Lui PC, Ma TK, Vong JS, Ng DC, Shi H-J, Lam WW. Papillary lesions of the breast-accuracy of core biopsy. Histopathology. 2010 Mar;56(4):481-8. PubMed PMID: 20459555 [pubmed]

[10]. Britton PD, Flower CDR, Freeman R, Sinnatamby R, Warren R, Goddard MJ, Wight DG, Bobrow L: Changing to core biopsy in an NHS Breast Screening Unit. Clin Radiol. 1997 Oct;52(10):764-7. PubMed PMID: 9366536 [pubmed]

[11]. Shannon J, Douglas-Jones AG, Dallimore NS: Conversion to core biopsy in prospective diagnosis of breast lesions: is it justified by results? J Clin Pathol. 2001 Oct;54(10):762-5. PMID: 11577122. [pubmed]

[12]. Carder PJ, Garvican J, Haigh I, Liston JC. Needle core biopsy can reliably distinguish between benign and malignant papillary lesions of the breast. Histopathology. 2005 Mar;46(3):320-7. PubMed PMID: 15720418 [pubmed]

[13]. Agoff SN, Lawton TJ: Papillary lesions of the breast with and without atypical ductal hyperplasia: can we accurately predict benign behavior from core needle biopsy? Am J Clin Pathol. 2004 Sep;122(3):440-3. PubMed PMID:15362376 [pubmed]

[14]. Ashkenazi I, Ferrer K, Sekosan M, Marcus E, Bork J, Aiti T, Lavy R, Zaren HA: Papillary lesions of the breast discovered on percutaneous large core and vacuum-assisted biopsies: reliability of clinical and pathological parameters in identifying benign lesions. Am J Surg. 2007 Aug;194(2):183-8. PubMed PMID:17618801 [pubmed]

[15]. Sydnor MK, Wilson JD, Hijaz TA, Massey HD, Shaw de Paredes ES: Underestimation of presence of breast carcinoma in papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core-needle biopsy. Radiology. 2007 Jan;242(1):58-62. PubMed PMID: 17090707 [pubmed]

[16]. Rizzo M, Lund MJ, Oprea G, Schniederjan M, Wood WC, Mosunjac M: Surgical follow-up and clinical presentation of 142 breast papillary lesions diagnosed by ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008 Apr;15(4):1040-7. PubMed PMID:18204989 [pubmed]

[17]. Simsir A, Waisman J, Thorner K, Cangiarella J: Mammary lesions diagnosed as “Papillary” by aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2003 Jun 25;99(3):156-65. PubMed PMID: 12811856 [pubmed]

[18]. Gomez-Aracil V, Mayayo E, Azua J, Arraiza A: Papillary neoplasms of the breast: clues in fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytopathology. 2002 Feb; 13(1):22-30. PubMed PMID: 11985565 [pubmed]

[19]. Lieske B, Ravichandran D, Wright D: Role of fine-needle aspiration cytology and core biopsy in the preoperative diagnosis of screen-detected breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2006 Jul 3; 95(1):62-6. PubMed PMID: 16755293 [pubmed]

[20]. Barra Ade A, Gobbi H, de L. Rezende CA, Gouvêa AP, de Lucena CE, Reis JH, Costa e Silva SZ: A comparison of aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy according to tumor size of suspicious breast lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008 Jan; 36(1):26-31. PubMed PMID: 18064684 [pubmed]

[21]. Westenend PJ, Sever AR, Beekman-de Volder HJC, Liem SJ: A comparison of aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy in the evaluation of breast lesions. Cancer. 2001 Apr 25;93(2):146-50. PubMed PMID: 11309781 [pubmed]

[22]. Hukkinen K, Kivisaari L, Heikkilä P, Von Smitten K, Leidenius M: Unsuccessful preoperative biopsies, fine needle aspiration cytology or core needle biopsy, lead to increased costs in the diagnostic workup in breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2008; 47(6):1037-45. PubMed PMID: 18607862 [pubmed]