Case Report

Multilocular radiolucency of anterior mandible

1Latha P. Rao, 2Rakesh S, 3Sherry Peter, 4Subramaniya Iyer

- 1Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Amrita School of Dentistry, Kochi, India.

- 2Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Amrita School of Dentistry, Kochi, India.

- 3Department of Head & Neck Surgery, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Kochi, India.

- 4Department of Head and Neck Surgery & Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Kochi, India.

- Submitted: October 18, 2012

- Accepted: November 28, 2012

- Published: November 30, 2012

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

A multilocular radiolucency in the anterior mandible in a 54 year old patient is presented and discussed as a clinic-pathologic conference. The differential diagnoses considered and algorithm used to arrive at the diagnosis with a review of literature is presented.

Keywords

Ameloblastoma, odontogenic keratocyst, aneurysmal bone cyst, central hemangioma, solitary (traumatic) bone cyst, central giant cell granuloma, and desmoplastic fibroma, ameloblastic carcinoma, malignant ameloblastoma.

Case Report

A 54 year old gentleman reported to the department for the evaluation of a swelling on the left side of lower jaw and mobility of lower front teeth. The swelling was first noted by the patient two years back and was gradually increasing in size since then. He did not complain of pain or numbness of teeth or neither lower lip nor he gave any history of antecedent trauma. His medical history was insignificant.

On clinical examination there was no swelling or asymmetry evident extra orally. He did not have any clinically palpable lymph nodes. Intraoral examination revealed a 2.5 X 2 cm, non tender, firm swelling on the lingual aspect of mandible extending from the central incisor to second premolar on the left side (Figure 1). There was a faintly palpable buccal cortical expansion also. The mucosa covering the swelling was normal in appearance. There were no pulsations or rise in temperature on palpation. The mandibular incisors, canines & left first premolar were nonvital.

Figure 1: Clinical photograph showing 2.5 X 2 cm, non tender, firm swelling on the lingual aspect of mandible from the central incisor to second premolar on the left side.

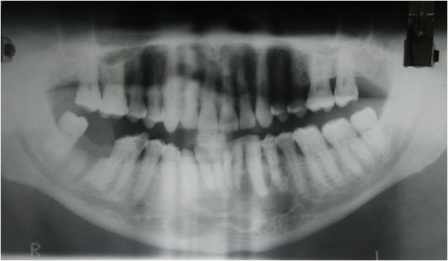

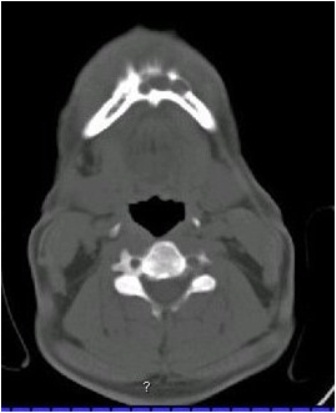

Orthopantomogram revealed a multilocular radiolucent lesion extending from left mandibular first premolar to right side canine region (Figure 2). The margins of the lesion were well defined and there were cortication inside the lesion. There was no periodontal ligament widening or root resorption or root displacement. CT scan showed a 3.5 X 3 X 3cm osteolyitc lesion in the mandibular symphysis region with a buccal perforation in the left canine region and lingual cortical perforations in the right side incisor - canine region (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Photograph showing Orthopantomogram revealing a well defined multilocular radiolucent lesion extending from left mandibular first premolar to right side canine.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of this well defined multilocular radiolucency in the anterior mandible was arrived at considering the history, site, clinical appearance & radiological findings. Odontogenic cysts and tumors, especially ameloblastoma and odontogenic keratocyst were first in our suspect list. The other probable diagnoses considered were odontogenic myxoma, and non-odontogenic lesions, such as aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC), central hemangioma, solitary (traumatic) bone cyst, central giant cell granuloma (CGCG), and desmoplastic fibroma, as anterior mandible is a common site for the occurrence for these entities. The probability of a primary intra alveolar carcinoma or metastatic lesion was also kept in mind.

Figure 3: Photograph showing CT scan showing an osteolytic lesion with buccal and lingual cortical perforations in the symphysis region.

The slow growth, lack of any palpable lymph nodes, and predominantly contained nature of the lesion pointed to the possibility of a benign lesion. Moreover there was no clinical evidence of any primary malignancy which could have metastasized to the facial skeleton.

The clinical presentation of an ABC in the jaws can include a firm swelling with or without tenderness, progressive enlargement, and occasionally perforation of the bony cortex. Unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesions with thinning of bony cortices and with well defined or diffuse margins have been reported [1]. Though the exact role of trauma in the etiopathology of ABC is not known, about 50-70% patients with ABC give a prior history of trauma, and the lesion usually manifests in the second or third decade of life [1]. The clinical & radiological picture of the present case correlated well with that of ABC, though the patient was in older age group and did not give any history of trauma.

Central hemangiomas of the jaws usually present as a multilocular radiolucency with a ‘honey-comb’ or ‘soap –bubble’ appearance. Patients are usually asymptomatic in the initial stages, unless it is a high flow lesion [2]. In high flow vascular lesion pain, swelling, discomfort, pulsation, tooth mobility, & slow oozing from gingival may be present [2].

Another probable entity in our list was solitary bone cyst (SBC) which is an intraosseous pseudocyst either empty or filled with serous or sanguinous fluid. Although SBC is usually seen in patients 10 to 20 years of age, it can also occur in older age groups. Most SBCs are asymptomatic and found during routine radiographic examination, but some patients present with pain, & swelling. Generally images show a unilocular homogenous osteolysis surrounded by condensation. Larger lesions appear multilocular with scalloped margins extending between the roots, which are unaffected by the lesion [3].

Central giant cell granuloma (CGCG) of jaws appears as well defined unilocular or multilocular radiolucency with undulating borders [4]. Clinically CGCG can grow to very large size before becoming symptomatic. Most cases of CGCG are detected by the third decade of life.

Desmoplastic fibroma is a myofibroblastic neoplasm, predominantly affecting mandible. Radiologically it can appear as a well defined radiolucency with multilocular pattern and can grow extensively before diagnosis [5]. But again this lesion is predominant in the initial decades of life.

Odontogenic myxomas are benign but locally invasive tumors originating from primordial mesenchymal tooth forming tissues [6]. Radiographically, the tumour is seen as a unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion with well-defined borders and fine bony trabeculae. Though it is the second most common odontogenic lesion, its incidence is approximately 0.07 new cases per million people per year [7].

Odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) is unique among odontogenic cysts (presently classified under odontogenic tumors by the WHO) for its locally aggressive nature and high recurrence rate [8]. Radiographically the lesion is most often multilocular radiolucency, surrounded by smooth or scalloped margins with sclerotic borders. The lesions predominantly grow in the cancellous bone in an anteroposterior direction before involving the cortical bones. The detection of the OKC is usually late as majority of patients are asymptomatic initially.

Ameloblastoma is the second most common odontogenic neoplasm, accounting for 11% of all odontogenic tumors in the jaw [9]. It is a benign but locally aggressive odontogenic tumour capable of extensive growth and disfigurement. The radiological appearance of ameloblastoma is multilocular ‘honey-comb’ or ‘soap- bubble’ radiolucency.

- The differential diagnosis of ABC, SBC central hemangioma and OKC were ruled out as aspiration with a wide bore needle yielded no aspirate. Similarly the diagnoses of CGCG, desmoplastic fibroma & odontogenic myxoma were clinically ruled out considering the rare nature of these lesions and the much younger age of occurrence than the present case.

- Ameloblastoma was our provisional clinical diagnosis as it is the most common cause for a slow growing, non tender, multilocular radiolucent lesion in the mandible.

Diagnosis & management

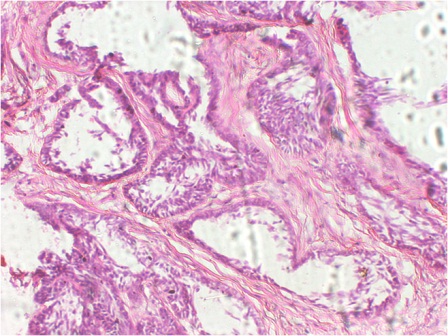

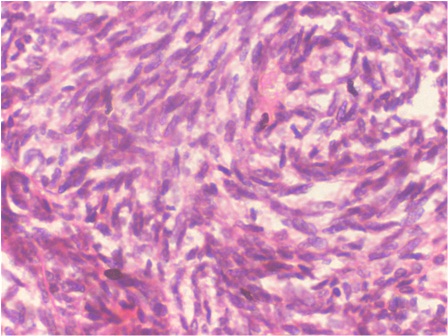

Incisional biopsy was carried out under local anesthesia. Crevicular incision was used to expose the labial surface of anterior mandible. Tissue was obtained from the left side canine region where the labial cortex had thinned down considerably. The histopathological examination revealed follicles of odontogenic epithelial cells with the peripheral palisaded cells exhibiting basilar hyperplasia. Stellate reticulums like cells were seen in the center of the follicles (Figure 4). In many areas, the basement membrane of the follicles was indistinct and the tumor cells which were seen to invade into the surrounding fibrous stroma, showed cytologic atypia (Figure 5). Based on these features, the diagnosis of ameloblastic carcinoma was made.

Figure 4: Photomicrograph showing ameloblastomatous islands with peripheral tall columnar cells and central stellate reticulum like cells. (H & E, 20x).

Figure 5: Photomicrograph showing the tumor cells invading the fibrous stroma, and exhibiting cytologic atypia. (H & E, 40x).

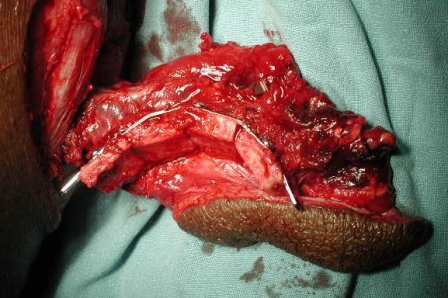

Accordingly a segmental mandibulectomy extending from right first premolar to left side second premolar was planned. The mandible was exposed using an upper transverse neck skin crease incision and intraoral sublabial incision. The mandible was exposed from right angle to left angle. Facial vessels were identified and prepared for anastomosis. As the resection would involve the symphyseal region of mandible, the reconstruction needed special attention. The recostruction plate was prebent on native mandible as the lower border was not expanded. Few bicortical screws were put on either side of anticipated bony cuts to mark the position of plate, after putting intermaxillary fixation. The plate was removed and kept aside. Mandibular right first premolar and left second premolar were extracted and bony cuts carried out through the sockets of these teeth. Free fibula flap with skin paddle, based on peroneal vessels was harvested from left lower limb according to the measurement of the defect. Fibula was ostoeotmised and fixed to the reconstruction plate with monocortical screws (Figure 6 & 7]. Pedicle was anatomosed with prepared facial vessels. The skin paddle was used to substitute the excised oral mucosal lining. The entire specimen was subject to histopathological examination, which was consistent with the incisional biopsy report of Ameloblastic carcinoma. The resection magins were complete and no soft tissue invasion was seen.

Figure 6: Intraoperative photograph showing the ostoeootmised fibula adapted to the prebent reconstruction plate.

No further treatment was suggested to the patient in view of the contained disease which was completely excised. Patient has been under regular follow up for 3 years and has been found to be disease free.

Figure 7: Photograph showing postoperative Orthopantomogram showing the ostoeotomised fibula used for reconstruction.

Discussion

The malignant transformation of ameloblastoma has been the subject of extensive discussion and controversy. Contrary to the anatomically benign ameloblastomas, those lesions which metastasize or show clinically aggressive course could be considered as malignant. These could be either malignant ameloblastoma or ameloblastic carcinoma. Malignant ameloblastoma show typical histological features of ameloblastoma in the primary tumour & metastatic deposits [9] whereas ameloblastic carcinoma exhibits histological features of both ameloblastoma and carcinoma [10]. WHO (2005) has defined ameloblastic carcinoma as a rare odontogenic malignancy that combines the histological features of ameloblastoma with cytological atypia, even in the absence of metastases [11].

The reports of incidence of ameloblastic carcinoma vary from 1.6 – 2.2% [12,13]. A review of the English-language literature by Yoon HJ (2009), from 1984 to 2008 revealed 104 reported cases of ameloblastic carcinoma, including 6 cases reported by the authors [14].

Most ameloblastic carcinomas appear to arise denovo, but a few cases arising from a preexisting ameloblastoma have been reported [15,16]. As long standing history of ameloblastoma was absent, in our case, the ameloblastic carcinoma could have arise de novo.

Clinically, ameloblastic carcinomas are more aggressive and are usually associated with perforation of the cortical plate, extension into surrounding soft tissue, numerous recurrent lesions and metastasis, usually to cervical lymph nodes [17]. The average reported age at identification of the pathology is 49.2years, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.97:1 [14]. The mandible is involved more than maxilla, with a ratio of 1.71:1, and most cases involve the posterior potion of the jaw [14]. In most cases, radiographic findings show ill defined radiolucency. However, focal radiopacity may be detected in radiolucent lesions [17,18].

In ameloblastic carcinomas arising from a recurrent ameloblastoma, the histological diagnosis may be simple, because most lesions have a malignant transition area coexisting with the benign ameloblastoma. When ameloblastic carcinomas arise de novo, diagnosis is not as simple. The detection of typical histological features of ameloblastoma, such as peripheral palisading, reverse polarity, and stellate reticulum like structure, along with features of cytologic atypia like hyperchromatism, large or atypical nuclei, increased mitotic index, necrosis, and neural and vascular invasion suggest the possibility of malignant transformation of an existing ameloblastoma [19]. Sometimes the cytological atypia may be so mild that it becomes necessary to correlate subtle histologic changes with biologic behavior to predict unusual aggressiveness in ameloblastoma [20]. The diagnosis of primary ameloblastic carcinoma (de novo ameloblastoma) was made in our case because of the presence of vague histological features of ameloblastoma with the tumour cells showing cytological atypia in the absence of a previous history of ameloblastoma.

When the diagnosis of an ameloblastic carcinoma is made, an assessment for metastases becomes important. Regional nodal metastasis and/or hematogenous dissemination are known to occur [21-23]. Seventy five percent of the distant metastases arise in the lungs whereas the rest occur in the bones, predominantly in skull, vertebrae, ribs and femur. In rare cases, brain or multiple bone metastasis have been reported [24,25]. A staged work-up consisting of a neck examination, a CT scan of the area and a chest radiograph becomes necessary. Detailed examination of our patient did not reveal any nodal or distant metastases.

The treatment of ameloblastic carcinoma requires jaw resection with 1.5- to 2- cm bony margins and neck dissection, prophylactic or therapeutic [24, 26,27]. Philip et al., (2005), advocate the use of adjuvant radiation in close or positive margins, extracapsular invasion, and perineural invasion and report a 3.3 years of disease free survival in 3 patients with ameloblastic carcinoma [28]. As our patient had histologically wide margins and the disease was confined to the mandible without soft tissue spread, the discussion in multidisciplinary tumour board favored a wait and watch policy.

Yoon et al., (2009) reported a recurrence rate of 28.3%, and 92.3%.in patients treated with radical surgical resection and conservative therapy respectively [14]. They found out a significant correlation between metastasis and prognosis, the 5-year survival rate of patients with metastasis was only 21.4%. Local recurrences are known to occur between 5 months and 151 months [19, 29]. Distant metastasis occur as early as 4 months and as late as 47 months after surgery [19, 30]. Therefore, long-term follow-up is mandatory to detect the late recurrence or metastasis. Our patient has been disease free for more than five years and is on regular follow-up.

Authors' Contribution

Latha P. Rao: Execution of surgery, literature search, putting together the manuscript.

Rakesh S: Histopathological diagnosis and helping with the histopathological part of manuscript.

Sherry Peter: Planning & execution of surgery, editing the completed manuscript.

S. Iyer.: Planning & execution of surgery, editing the completed manuscript.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Ethical Considerations

Patients consent for publication of this case report was obtained.

Funding

None

References

[1]. Motamedi MH, Navi F, Eshkevari PS, Jafari SM, Shams MG, Taheri M, et al. Variable presentations of aneurismal bone cysts of the jaws: 51 cases treated during a 30-year period. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;66:2098-103. [Pubmed].

[2]. Cheng NC, Lai DM, Hsie MH, Liao SL, Chen YB. Intraosseous hemangiomas of the facial bone. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117: 2366-72. [Pubmed].

[3]. Harnet JC, Lombardi T, Klewansky P, Rieger J, Tempe MH, Clavert JM. Solitary bone cyst of the jaws: a review of the etiopathogenic hypotheses. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;66:2345-2348. [Pubmed].

[4]. Jadu FM, Pharoah MJ, Lee L, Baker GI, Allidina A. Central giant cell granuloma of the mandibular condyle: a case report and review of the literature. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2011;40:60-4. [Pubmed].

[5]. Said-Al-Naief N, Fernandes R, Louis P, Bell W, Siegal GP. Desmoplastic fibroma of the jaw: a case report and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006;101:82-94. [Pubmed].

[6]. Nagai N, Takeshita N, Nagatsuka H, Inoue M, Nishijima K, Nojima T, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma: case report and review. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991; 20:460-3. [Pubmed].

[7]. Simon EN, Merkx MA, Vuhahula E, Ngassapa D, Stoelinga PJ. Odontogenic myxoma: a clinicopathological study of 33 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;33: 333- 337. [Pubmed].

[8]. Stoelinga PJ: The treatment of odontogenic keratocysts by excision of the overlying, attached mucosa, enucleation, and treatment of the bony defect with Carnoy solution. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 63: 1662-1666. [Pubmed].

[9]. Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ. Oral Pathology: Clinical-Pathologic Correlation. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1989: pp. 363–374.

[10]. Elzay RP. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaws. Review and update of odontogenic carcinomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol (1982); 54(3):299–303. [Pubmed].

[11]. Sciubba J. Odontogenic tumours. In: Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours, pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. p. 287-93.

[12]. Jing W, Xuan M, Lin Y, Wu L, Liu L, Zheng X, et al. Odontogenic tumours: a retrospective study of 1642 cases in a Chinese population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;36: 20-5. [Pubmed].

[13]. Ladeinde AL, Ajayi OF, Ogunlewe MO, Adeyemo WL, Arotiba GT, Bamgbose BO, Akinwande JA. Odontogenic tumors: a review of 319 cases in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005; 99:191-5. [Pubmed].

[14]. Yoon HJ, Hong SP, Jae-Il Lee , Lee SS, Hong SD. Ameloblastic carcinoma: an analysis of 6 cases with review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 108(6): 904-913. [Pubmed].

[15]. Slootweg PJ, Müller H. Malignant ameloblastoma or ameloblastic carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984; 57:168-76. [Pubmed].

[16]. Abiko Y, Nagayasu H, Takeshima M, Yamazaki M, Nishimura M, Kusano K, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma ex ameloblastoma:report of a case—possible involvement of CpG island hyper- methylation of the p16 gene in malignant transformation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 103: 72-6. [Pubmed].

[17]. Akrish S, Buchner A, Shoshani Y, Vered M, Dayan D. Ameloblastic carcinoma: report of a new case, literature review, and comparison to ameloblastoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 65:777-83. [Pubmed].

[18]. Naik V, Kale AD. Ameloblastic carcinoma: a case report. Quintessence Int 2007; 38: 873-9. [Pubmed].

[19]. Hall JM, Weathers DR, Unni KK. Ameloblastic carcinoma: ananalysis of 14 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;103:799-807. [Pubmed].

[20]. Lau SK, Tideman H, Wu PC. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the jaws. A report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998; 85:78-81. [Pubmed].

[21]. Schweitzer FC, BarnfieldWF. Ameloblastoma of the mandible with metastasis to the lungs: report of a case J Oral Surg 1943; 1: 287 – 295.

[22]. Laughlin EH. Metastasizing ameloblastoma.Cancer 1989; 64: 776-780. [Pubmed].

[23]. Witterick IJ,Parikh S, Mancer K, Gullane PJ.Malignant ameloblastoma. Am J Otolaryngol 1996;17:122- 126. [Pubmed].

[24]. Datta R, Winston JS, Diaz-Reyes G, Loree TR, Myers L, Kuriakose MA, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma: report of an aggressive case with multiple bony metastases. Am J Otolaryngol 2003;24:64-9. [Pubmed].

[25]. Goldenberg D, Sciubba J, Koch W, Tufano RP. Malignant odontogenic tumors: a 22-year experience. Laryngoscope 2004; 114: 1770-4. [Pubmed].

[26]. Zwahlen RA, Grätz KW: Maxillary ameloblastomas: a review of the literature and of a 15-year database. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2002, 30(5):273-9. [Pubmed].

[27]. Benlyazid A, Lacroix-Triki M, Aziza R, Gomez-Brouchet A, Guichard M, Sarini J. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla: case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod (2007); 104(6):e17–e24. [Pubmed].

[28]. Philip M, Morris CG,Werning JW,Mendenhall WM. Radiotherapy in the treatment of ameloblastoma and ameloblastic carcinoma. J HK Coll Radiol 2005; 8:157-161.

[29]. Lee L, Maxymiw WG, Wood RE. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla metastatic to the mandible. Case report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1990;18: 247-50. [Pubmed].

[30]. Bruce RA, Jackson IT. Ameloblastic carcinoma. Report of an aggressive case and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1991;19: 267-71. [Pubmed].