Case report

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of chest wall in a young adult: comprehensive work-up, nine months post surgery follow-up and adjuvant chemotherapy

1Amit Nandan Dhar dwivedi, 2Prashant K Gupta, 2Rohit Bhargava, 3Kumkum Gupta

- 1Department of Radiodiagnosis and Imaging, Institute of Medical Sciences,Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, India

- 2Department of Radiodiagnosis and Imaging, Subharti Medical College, Meerut 250002, India

- 3Department of Anaesthesia, Subharti Medical College, Meerut. 250002, India

- Submitted: February 8, 2012;

- Accepted February 24, 2012

- Published: February 26, 2012

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction:

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor is a malignant small round cell tumor affecting the thoraco-pulmonary region, also known as Askin tumor.

Case report:

A seventeen year old male presented with recent onset breathlessness of one and half month duration which was progressive and increased on exertion. After physical and systemic examination he was subjected to chest skiagram, contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Skiagram of chest showed a well circumscribed mass in upper zone of right lung. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) showed malignant small round cell tumor. Clinical, radiological and cytological findings led to the diagnosis of round cell tumor-primitive neuroectodermal tumor of chest wall. The patient underwent radical surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy. The patient was followed up for nine months. During this period he was clinically and radiologically disease free.

Conclusions:

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor is malignant small round cell tumor affecting thoraco-pulmonary region. A standardized multimodality treatment is more beneficial. Long term survival can be achieved with both aggressive local and adjuvant multidrug chemotherapy

Introduction

Primitive neuroectodermal tumors are a group of highly malignant tumors composed of small round cell tumors of neuroectodermal origin that effect soft tissue and bone. They are extremely aggressive and metastasize rapidly and widely. They carry identical chromosomal translocations to Ewing’s sarcoma. Although the clinical and pathological characteristics of primitive neuroectodermal tumors are well known, the radiological features have not been much reported. The malignant small round cell tumors of the thoraco-pulmonary region were first described by Askin in 1979. However, these tumors are rare and often occur in childhood or adolescence. Chest radiography, most often used for initial evaluation, can be helpful for detecting cortical destruction but computed tomography is

more sensitive sthan chest radiography for detecting calcified tumor matrix and cortical destruction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) often allows more accurate delineation and localization of the tumor and is helpful for determining the presence and extent of tumor invasion and tissue characterization. Although the imaging features of many malignant chest wall tumors are nonspecific, knowledge of the typical radiologic manifestations of these tumors often enables their differentiation from benign chest wall tumors and occasionally allows a specific diagnosis to be suggested.

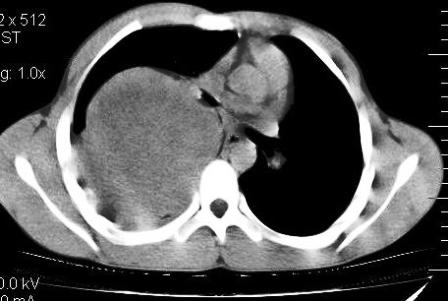

Figure 1: CECT thorax showing extra-parenchymal mass right upper and middle hemithorax

This case report highlights complete diagnostic work up of the patient from skiagrams to MRI followed by tissue diagnosis, radical surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. A nine month follow up sheds light on the biological behavior of this unpredictable and aggressive tumor.

Case Report

A seventeen year old male presented with recent onset breathlessness of one and half month duration which was progressive and increased on exertion. He was a nonsmoker with no history of exposure to any occupational or inorganic dusts. The physical examination revealed averagely built person and respiratory system revealed decreased air entry in right lung. Routine blood investigations were within normal limits. Pulmonary function tests revealed early small airway obstruction and moderate restriction. Echocardiography was normal. Chest skiagrams showed a well define homogenous opacity involving upper and middle zone of right lung. Contrast enhanced computed tomography(CECT) of thorax revealed a large (15 x 11 x 11 cm) well defined non homogenous mass in the right upper

and middle hemi thorax near the hilum with broad base towards posterior and medial chest wall and right paravertebral region significantly displacing and distorting the right lung parenchyma (upper lobe) anteriorly(Figure 1).

Figure 2: CECT thorax showing involvement of pleura and pleural reaction

The lesion showed sharp interface with the adjacent lung parenchyma, with no evident parenchymal changes. Involvement of posterior right pleura was noted with presence

of mild pleural effusion and pleural thickening (Figure 2). The lesion showed heterogeneous post contrast enhancement with multiple hypo attenuating regions. There was permeative pattern of erosion of right 5th rib posterior portion with indistinct inner cortex (Figure 3). There was no extrathoracic, intraspinal or neural formainal extension of lesion. Partial displacement and mass effect was noted over carina, right major bronchus, thoracic esophagus with no evident invasion or encasement. No mediastinal lymphadenopathy

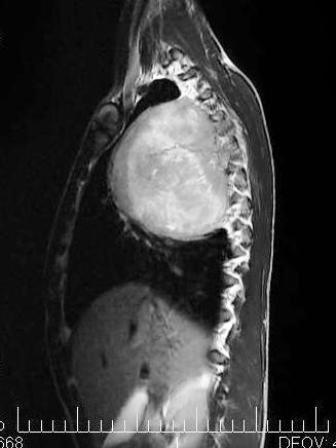

was noted. Left lung field and aerated right lung, retrosternal area, liver, spleen, pancreas and both adrenals appeared normal. An additional MRI was done to get additional information about chest wall, mediastinal and soft tissue invasion and to confirm the findings (Figure 4,5).

Figure 3: Erosion and involvement of posterior aspect of right fifth rib

Figure 4: MRI coronal plane showing excellent soft tissue delineation

Figure 5: MRI sagittal plane showing antero-posterior extension of tumor

Figure 6: Chest radiograph at six months does not show evidence of residual disease

The fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed compressed trachea and blurred carina due to extra luminal compression. Right bronchial anatomy was distorted due to extrinsic compression (fish mouth opening) with no intra bronchial extension. Bronchial lavage was negative for ZN stain, Gram stain, and KOH mount. The patient underwent radical thoracotomy with wide excision of right mediastinal mass under general anesthesia. Postoperative period was uneventful. Excised tumor with rib showed features consistent with lung sarcoma. Tumor was infiltrating the capsule, adjacent muscles, soft tissue and lung parenchyma. Rib resected margin was involved. Histologically, the specimen showed discrete round cells having high nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio, round hyperchromatic nuclei with 1-3 small nucleoli.

Cytoplasm was scanty to moderate and showed fine vacuolization in some of the cells. The cells also showed anisonucleosis. Immunohistochemical stains were performed on sections from the paraffin-embedded blocks. Tumor cells showed abundant intra-cytoplasmic PAS positive material. The tumor showed a strong and diffuse positivity with vimentin and CD99 and focal immunostaining with NSE and neurofilaments. As the diagnosis of primitive neuroectodermal tumor was established, and wide surgical excision of the tumor was already been done, the patient was referred for six cycles of chemotherapy which included cyclophosphamide (900 mg),vincristine (2 mg), adriamycin (80 mg), dacarbazine (1400 mg). Our patient did not receive any radiotherapy. Chest skiagrams(Figure 6) and CT scan were taken during the patient . The patient was clinically and radiologically disease free during nine months of follow up.

Discussion

Askin and Rosai in 1979 described a rare primitive neuroendocrine tumor involving the thoracopulmonary region, common in young females. Primitive neuroendocrine tumours (PNET) and Ewing’s sarcoma are small round cell tumours of neural origin. PNET are rare thoracic tumours found in adolescent or young adults and asymptomatic until advanced stage and hence have poor prognosis [1]. They are believed to develop from the peripheral nerves and highly aggressive neoplasms of the thorax with average survival of eight months, although occasional long term survival can be as long as 96 years. The PNET cells do not produce biologically active substances detectable in the blood and urine. They carry identical chromosomal translocations t(11; 22) (q 24; q 12) as seen in Ewing sarcoma. PNET is a rare undifferentiated sarcoma which is believed to have its origin in embryonal migrating cells from the neural

crest and develops as solitary mass or multiple masses in thoracic area, with rapid growth that may involve pleura. Pain is the only or main symptom in 60% of cases. In the thoracic area, these tumors are invasive and prone to destroying bone, invading the retroperitoneal space, and spreading to lymph nodes, adrenals and liver.

Once resected, they recur with extremely high frequency. Image diagnosis is based on chest skiagrams, CT scan and MRI. The fine needle aspiration biopsy identifies the presence of small cells with neurosecretory granules, microtubules and cytoplasmic extensions. Characteristics PENT pathologic findings include compact nests of small cells, Homer-Wright pseudo rosettes with an acidophilic core of neurofibrillary characteristics, and uptake of neuron specific enolase stain. The treatment for PNET must consist, wherever possible, radical resection supplemented with radiotherapy (3,500 to 5,500 Rads) and aggressive chemotherapy (carboseamide, vincristine, doxorubin, cisplatinum, methotrexate, bleomycin and dimethyltriazenyl imidazole carboseamide).

These tumors peak (64%) in the latter half of the second decade of life but 27% of cases occur in the first decade of life, and 9% occur in the third decade of life. Cases occurring later in life are infrequent [2]. The incidence in males is slightly higher than in females (1.1: 1). Kushner et al reported that the disease arose from the chest wall (33.3%), pelvis (22.2%), paraspinal region (13.0%), retroperitoneum (11.1%), limbs (9.3%), abdomen (7.4%), neck (1.9%), and unknown site (1.9%) [3]. Similar results were supported by Kennedy et al in the year 2005 [4]. Less than 25% presented with pulmonary involvement, either alone or in combination with a chest wall mass. An overall 5-year survival rate of 60% has been described in patients with localized tumors with average survival of eight months, although occasional long term survival can be as long as 96 years [5]. The fact that PNET and Ewing’s

sarcoma are considered to be similar tumors with different degrees of neuroectodermal differentiation suggests that PNET patients should also undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy with Ifosfamide-Etoposide [6]. There are an increasing number of reports supporting multimodality protocols for the treatment of PNET, which include preoperative chemotherapy. Unfortunately, data mainly exist for children and adolescents, and take into consideration the inhibition of bone growth caused by radiotherapy. Most studies suggest that neoadjuvant treatment is essential to avoid a mutilating surgical procedure and intraoperative tumor cell dissemination [7]. The survival rate associated with PNET is similar to that of osseous Ewing’s tumor when Ewing’s-directed combined modality therapy is used (pre- and postoperative chemotherapy, surgery, and adjuvant radiotherapy in cases of large lesions and poor response to induction chemotherapy) [8].

Reports suggest that multimodality treatment is more beneficial, and surgery should be avoided in the first stage of therapeutic management, even if resection is obviously feasible. Surgery should be performed after chemotherapy, even if there is a complete response, because scattered malignant cells may still be found in the scar tissue [8]. After curative resection, postoperative chemoradiotherapy regimens are mandatory because of the particularly high risk of both local recurrence and distant metastases [9,10].

The present case describes one of the few reported cases of PNET in an adult. The clinical presentation of short duration, chest skiagram, CT scan and MRI were diagnostic for pulmonary tumor and FNAC was diagnostic for round cell tumor with a high suspicion of malignancy. Open radical thoracotomy with excision of the removable tumor proved the diagnosis of PNET. Surgery was followed by chemotherapy, with an excellent result.

Surgery and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy are universally accepted steps in PNET treatment, but more data are needed to support the necessity of neoadjuvant chemotherapy [10,11,12]. Since it is a rare and extremely aggressive malignancy, multidisciplinary protocols should be used to achieve optimal results [13,14]. After completion of treatment, a thorough follow-up at short intervals is indispensable. In cases of recurrence, resection of the malignancy is feasible [15].

Conclusions

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor is aggressive and lethal, hence should be considered in the differential diagnosis of thoracic tumors regardless of the age of the patient. Once the diagnosis of the PNET has been made, early wide excision of the tumor, along with multimodality chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be planned for long term survival. Invasion at the time of diagnosis carries poor prognosis.

Author’s contribution

AND: Designed and conceived the study, edited the manuscript.

PKG: Literature review and preparation of draft manuscript

RB: Preparation of manuscript and intellectual content

KG: Literature search and preparation of draft manuscript

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Ethical considerations

The written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Funding

No financial support was received for this study

References

[1]. Askin FB, Rosai J, Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Mc Alister WH. Malignant small cell tumor of the thoracopulmonary region in childhood. Cancer 1979; 43: 2438-2451.

[2]. Etienne Mastroianni B, Falchero L, Chalabreysse L, Loire R, Ranchère D, Souquet PJ, Cordier JF. Primary sarcomas of lung: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Lung Cancer 2002; 38: 283-289.

[3]. Kushner BH, Hajdu SI, Gulati SC, Erlandson RA, Exelby PR, Lieberman PH. Extracranial primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Cancer 1991; 67: 1825-1829.

[4]. Kennedy JG, Eustace S, Caufield R, Fennelly DJ, Hurson B, O'Rourke KS. Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma: a case report and review of literature. Spine 2000; 25: 1996-1999.

[5]. Nesbit ME Jr, Gehan EA, Burgert EO Jr, Vietti TJ, Cangir A, Tefft M, Evans R, Thomas P, Askin FB, Kissane JM, et al. Multimodal therapy for the management of primary, non-metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma of the bone: a long-term follow-up of the first intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 1990; 8: 1664-1674.

[6]. Ushigome S, Machinani R, Sorensen PH. Ewing sarcoma/ primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET). In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, (editors). Pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. IARC Press, Lyon, 2002:297–300.

[7]. Zimmermann T, Blütters-Sawatzki R, Flechsenhar K, Padberg WM. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: challenge for multimodal treatment. World J Surg 2001; 25:1367–1372.

[8]. Gururangan S, Marina NM, Luo X, Parham DM, Tzen CY, Greenwald CA, Rao BN, Kun LE, Meyer WH. Treatment of children with peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor or extraosseous Ewing’s tumor with Ewing’s-directed therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1998; 20:55–61.

[9]. Christiansen S, Semik M, Dockhorn-Dworniczak B, Ro¨tker J, Thomas M, Schmidt C, Jurgens H, Winkelmann W, Scheld HH. Diagnosis, treatment and outcome of patients with Askin-tumors. Thorac Cardiov Surg 2000; 48: 311–315.

[10]. Krassas A, Mallios D, Kalkandi P, Boulia S, Reveliotis C, Sepsas E. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the thoracic wall in a 48-year-old man. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2010; 18: 285-287.

[11]. Sallustio G, Pirronti T, Lasorella A, Natale L, Bray A, Marano P. Diagnostic imaging of primitive neuroectodermal tumor of chest wall (Askin tumor). Pediatr Radiol 1998; 28: 697-702.

[12]. Gaude GS, Malur PR, Kangale R, Anurshrtru S. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the lung in an adult. Lung India 2009; 26:89-91.

[13]. Parikh M, Samujh R, Kanojia RP, Mishra AK, Sodhi KS, Bal A. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the chest wall in childhood: Clinico-Pathological significance, management and literature review. Chang gung Med J 2011; 34: 213-217.

[14]. Hage R, Duurkens VA, Seldenrijk CA, Brutel de la Rivière A, van Swieten HA, van den Bosch JM. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002; 124: 833-836.

[15]. Hari S, Jain TP, Thulkar S, Bakhshi S. Imagimg features of peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumours. Br J Radiology 2008; 81:975-983.