Original Article

Clinical outcome of Vulvar Carcinoma: 10-years’ Experience from a Tertiary Care Center of Pakistan

*,I Haider, *KU Rehman ,, U Masood, *A Rashid, *MA Ilyas*K Saeed*, S Usman,*,A Rashid, *, SA Abbas*U Majeed, *, A Jamshed*S Hameed

- *Radiation Oncology Department Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Center, Lahore, Pakistan.

- Submitted Thursday, July 24, 2014

- Accepted:Friday, July 25, 2014

- Published Friday, August 15, 2014

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Purpose

Retrospective analysis was aimed to analyze patient’s characteristics and outcome with vulvar carcinoma treated at our center.

Material and Methods

All patients with histopathological proven carcinoma vulva, treated at our hospital during the year 2002-2011, were retrieved and analyzed retrospectively. Clinical presentation, treatment given, survival and complications were recorded. Overall survival was determined with respect to stage of disease, histology, grade and lymph node status.

Results

29 patients with histologically proven squamous cell carcinoma were eligible for this analysis. The median age was 58 years (range 32 to 75 years) and median follow up was 29 months (range, 9 to 131 months). The patients with squamous cell carcinoma had Grade-I in 16 cases, Grade-II in 9 and Grade-III in 4 patients. Five patients presented with FIGO stage I, 7 in stage II, 10 in stage III and 7 with stage IV-A. 12 patients underwent surgery (simple vulvectomy 2, radical vulvectomy and inguinal lymph node dissection 10. Ten patients received post-operative chemoradiation and 5 of them were received post-operative radiotherapy alone. 17 patients treated with definitive chemoradiation and 3 of them have received radiotherapy alone. All failures occurred during first 2 years after completion of treatment. The 5 years overall survival was 44.8% for all stages. Stage and nodal positivity were found to have significant impact on overall survival.

Conclusion

Overall survival is quite comparable to the reported series. Majority of patients presents in locally advanced stages so multidisciplinary approaches should be used to have better outcome.

Key words

Introduction

Carcinoma of the vulva is one of the rare malignancies of the

female genital tract as it accounts for only 3-5% of all gynecological

malignancies. [1] Elderly post-menopausal females are mostly affected with the median age at diagnosis of 60years (range 50-70 years), though its trend is also on the rise in younger population and 10-15% cases are diagnosed under 40years of age possibly due to HPV infection

[2 3]. Vulvar carcinoma is also reported in HIV infected patients

[4 5]. Majority of vulvar cancers are of squamous cell variety accounting for more than 90% of cases. Other rare malignant subtypes of vulvar area include Basal cell carcinomas, melanomas and sarcomas which in total comprise less than 5-7 %

[6].

Different surgical series have shown that inguinal nodes are involved quite frequently reporting a figure of 6-50% and among these patients with positive inguinal nodes, pelvic nodal positivity also increases up to 30%

[7]. In literature different parameters have been described which determine prognosis in vulvar cancer, the most significant among those is the presence and number of inguinal lymph nodes involvement

[8].

Historically surgery has been the mainstay for this disease with post-op radiotherapy reserved for close or positive margin and nodal positivity. Though, routinely practiced surgery Radical vulvectomy with bilateral inguinofemoral lymph node dissection improved overall survival but on the expense of significant post-operative morbidities, disfigurement and mutilation

[9 10]. Such complications forced oncologists towards more conservative surgery. Now a day wide local excision with adequate margins and ipsilateral inguinal dissection is routine practice for unilateral tumors. Locally advanced disease has always been a major therapeutic challenge.

In recent years multimodality treatment concept has emerged on oncology horizon and has gained much popularity in loco regionally advanced disease, such as fixed or ulcerated nodes

[11 12 13]. Attempts to remove such advanced disease have yielded dismal results in terms of survival. For such unresectable disease progression is inevitable. Combined modality approach using concomitant chemo radiation followed by surgery has been explored extensively.

Despite good functional outcome and better local control with this approach still compliance is poor due to significant side effects. To cope with compliance issue, split course chemo radiation has also been used with acceptable toxicity and comparable outcome

[14]. Illiteracy and socioeconomic constrains in developing countries like Pakistan are major factors for late presentation which in turn leads to loco regionally advanced disease. So management is always hampered by such factors.

Objective of this retrospective analysis is to determine the patient’s characteristics and disease outcome in terms of prognostic factors and overall survival in our population.

Materials and Methods

Records of all patients with vulvar cancer who presented to Radiation department Shaukat Khanum Cancer Hospital & Research Centre (SKMCH & RC) between 1st Jan 2002 and 31st Dec 2011 were analyzed retrospectively. Ethical clearance was obtained from ethical committee of SKMCH &RC, Lahore, Pakistan. Prior to collection of the case notes, clinical details, operative notes, diagnostic imaging reports and pathology reports of all patients were reviewed from a software programme, Hospital Information System (HIS). Stages were assigned according to the 2009 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system.

All these patients were evaluated clinically by gynecologist and radiation oncologist in separate clinics to establish the stage of the disease. Baseline work up including routine hematological (i-e complete blood counts, liver & renal function tests, serum chemistry) and radiographic investigations (i-e Chest X-ray, Ultrasonography abdomen and MRI-Pelvis) were done in every patient for treatment planning purposes. The intent and type of treatment modality was decided in the multidisciplinary meeting comprising radiation oncologist &gynecologist. Surgery was the primary treatment modality for early stage disease with post-operative radiation therapy (PORT) when indicated i-e positive or close margins (<5mm), lymphovascular invasion, extracapsular spread and gross residual nodal disease. Different treatment options were opted like radical vulvectomy followed by PORT, Pre-Op chemoradiation followed by surgery or definite chemo radiation for loco regionally advanced disease.

Radiotherapy fractionation schedule and technique was used according to the clinico-pathological characteristics of the patients. For post-op microscopic and primary gross disease definitive RT was delivered. The radiation dose was 45-50Gy in adjuvant setting 60Gy to residual/gross disease, with conventional fractionation (180-200cGy/Fraction 5 days a week). Two symmetric AP-PA fields were used covering the both primary disease and draining lymph nodes (Inguinal and Pelvic) on linear accelerator. Appropriate thickness of bolus was used for palpable nodes. Patients who were treated with definite concurrent chemo radiotherapy, a gap of two weeks was planned after 3060cGy/17 fractions to avoid the unnecessary treatment interruption secondary to skin toxicity. Electrons were used boosting the primary and palpable inguinal node regions to bring dose to 60Gy. Chemotherapy regimens included either weekly CDDP 40mg/m2 alone or CDDP/5FU Cisplatin 75mg/m2 at D1 and 5FU 1000mg/m2 D1-4 in week 1 and week 5 respectively. All patients were followed at weekly interval during the course of chemoradiotherapy to assess the hematological and non-hematological toxicities.

examination and CT/MRI was advised if clinically indicated or patients having subjective symptoms regarding disease. First follow up was planned 6-8 weeks after completion of radiotherapy and then 3 monthly for 1st year & then 4-6 monthly in subsequent years.

Kaplan Meier survival method was used to get OS and DFS from SPSS version 19.5 .RTOG criteria being used as toxicity assessment tool. All patients were analyzed and patients who lost to follow up were contacted via telephone. Univariate and multivariate analysis was done using log rank test and cox regression model respectively.

Results

Characteristics of the 29 evaluable patients are described in Table 1. All patients were histologically proven squamous cell carcinoma with median age 58 years (range 32 to 75 years). The median follow up was 29 months (range, 9 to 131 months). Among 29 patients 16 had Grade-I, 9 with Grade-II and Grade-III was found in 4 patients. Five patients presented with FIGO stage I, 7 in stage II, 10 in stage III and 7 with stage IV-A. Twelve patients underwent surgery (Simple vulvectomy 2, radical vulvectomy with inguinal lymph node dissection 10. Lymph node dissection was performed in 10 patients. Patients who underwent primary surgery, 10 received adjuvant radiotherapy. Five patients received post-operative chemo radiation and 5 of them were treated with post-operative radiotherapy alone. Seventeen patients underwent definite radiotherapy; 14 of them received concurrent chemotherapy. Chemotherapy regimens used were Cisplatin/5FU in 8 patients and weekly Cisplatin 40mg/m2 in 6 patients. Median radiation dose was 56Gy (range, 45 to 76Gy). Patients who were treated with definite chemoradiation, majority (12/14) had completed their treatment without any treatment interruptions. The main causes of unexpected withdrawal were poor tolerance due to skin reactions.

|

Attribute

|

|

Age

|

Years

|

|

Median

|

58

|

|

Range

|

32-75

|

|

FIGO Stage

|

No. of

Patients

|

|

I

|

5

|

|

II

|

7

|

|

III

|

10

|

|

IV

|

7

|

|

Histological Grade

|

No. of

Patients

|

|

Well differentiated

|

16

|

|

Moderately differentiated

|

9

|

|

Poorly

differentiated

|

04

|

|

Lymph Node Status

|

% of

Patients

|

|

Node

Positive

|

42

|

|

Node Negative

|

58

|

|

Treatment Groups

|

No. of

Patients

|

|

Surgery alone

|

2

|

|

Surgery + PORT/POCRT

|

5

|

|

Pre-op CRT/RT +

Surgery

|

5

|

|

Definite RT/CRT

|

17

|

|

Type of Surgery

|

No. of

Patients

|

|

Simple vulvectomy

|

2

|

|

Radical vulvectomy

|

10

|

All of 27 patients who received PORT or Definite RT/CRT had acute skin complications. 14 patients had desquamation of skin. Skin toxicity G-111, causing treatment breaks longer than 1 week occurred in 2 patients. Out of 17 patients who were treated with concurrent chemoradiation 4 had G-III neutropenia, who were treated with Cisplatin/5FU regimen. Of the 10 patients who underwent inguinal lymph node dissection 2 developed lymphocele and 3 developed lymphedema.

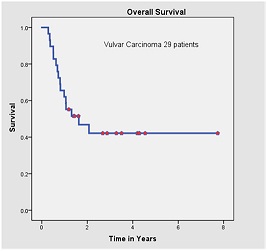

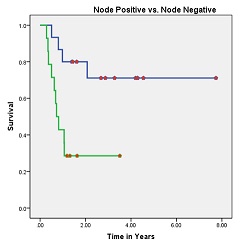

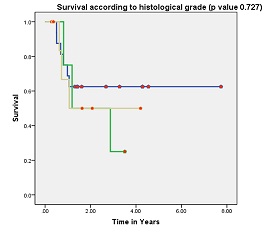

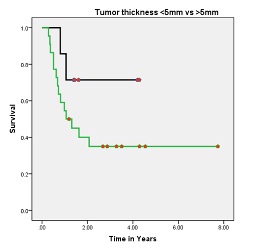

Out of 29 patients, 14 (58.6%) were alive with no evidence of disease. All the recurrences were within first two years after the completion of treatment. Of the 15 patients who died, 14 had failure (12 were confined to locoregional sites and 2 had distant failure). Site of distant metastasis were lung and liver. One patient developed second primary (squamous cell carcinoma left buccal mucosa) 6 months after completion of her treatment. She was died because of progressive left buccal mucosa disease. The 5-years OS for all stages was 44.8% [Figure 1]. The 5-year OS in stage I, II, III, IV-A was 90, 79, 44 and 14% respectively. Pathologically node negative patients had significant superior overall survival than node positive patients (73% vs. 29%, respectively; p value 0.006) [Figure 2]. Histological grade and tumor thickness were not significant (p value 0.727 and 0.17 respectively) [Figure 3] [Figure 4]. On univariate analysis FIGO Stage and nodal status were statistically significant factors but on multivariate analysis none of analyzed factors had significant p value.

Figure-1:Kaplan Meier survival analysis; Overall survival of patients with vulvar carcinoma.

Figure-2: Overall survival of patients with node positive (green) and node negative status (p value 0.006)

Figure-3: Overall survival according to histological grade (p value 0.727).Green-

Grade III, Blue- Grade I, Yellow- Grade II

Figure-4: Overall survival of patients with primary tumor thickness<5

(black) vs>5mm (green) (p value: 0.17)

Discussion

In developing countries, where most cancer patients present in locally advanced stages, vulvar carcinoma is rarely reported. There is no study from Pakistan but few retrospective analyses from India have been reported in literature

[15 16]. Ours is the first retrospective analysis from Pakistan.

From this study, we make several important observations first, median age at presentation is less as compared to reported series. Second, all treatment failures occurred during first 2 years after the completion of treatment. Thirdly, patients who underwent surgery have better outcome as compared to those who were treated with radical chemoradiation (most likely the smaller tumors /early stage disease had surgery done, so better outcome).

The median age of presentation in our study (58 years) is less a compared to the international literature, but it is similar to the one reported by Bafna et al. from India

[15]. Almost half of the patients in our analysis presented in locally advanced stage (Stage III, IV) of the disease. This figure is less as compared to that reported in both Indian series

[15 16]. In our analysis, FIGO staging and node positivity were significant prognostic factors for survival which is similar with the results of Sharma et al. who have shown that stage and presence of positive nodes at presentation significantly affects the prognosis

[16]. Stage III, IV patients had poor outcome as compared to stage I, II in our study. In 1991, the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) reported a survival analysis of 588 patients and observed that 5-year survival in stage I, II, III and IV was 98, 85, 74 and 31% respectively.

Tumor thickness, age>65 years and histological grade have been regarded as significant prognostic factors in several series but it was not found significant in our series

[8]. In our series, patient with primary tumor thickness <5mm had better outcome as compared to patient with tumor thickness >5mm but statistically p-value was not significant. One explanation for this difference is fewer number of patients with <5mm tumor thickness.

our series, patients who were treated primarily with surgery had better survival as compared to those were treated with radical chemoradiation. Fourteen patients who had recurrence, 10 of them were treated with radical chemoradiation and 4 were managed with surgery. Radical vulvectomy was the commonest surgical procedure in our study.

The recent trend is shifting toward more conservative approaches with use of pre-operative radiotherapy or chemoradiation. Results from Phase II prospective trials have shown that pre-operative chemoradiation is not only feasible but also reduce the need for more radical surgery including primary pelvic exenteration

[14]. None of our patients received pre-operative chemoradiation. This should be the point of future investigations in our population, as most of our patients are presenting in locally advanced disease.

Adjuvant radiotherapy reduces rate of local recurrences in patients with close (<8mm) or positive margins, from 58 to 16%

[17]. In a GOG study, [18] patients with positive inguinal nodes after radical vulvectomy and inguinal node dissection were randomized to subsequent pelvic node dissection versus PORT. Dose of radiation was 45-50Gy delivered bilaterally to pelvic and inguinal nodes using anterior and posterior opposing fields. The study had shown significant survival advantage for patients receiving PORT (2-year survival 68% vs. 54%, p=0.03) and lower rates of relapse (5% vs. 24%, p= 0.02). The planned split course chemoradiation scheme was adopted by the findings of Thomas and colleagues that acute toxicity was more severe in chemotherapy arm, and could be diminished by a split course regimen while still achieving a superior outcome

[14].

Addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy was started by positive results reported in other tumor sites. Theoretically, if the net effects of radiation-drug interactions in tumors are synergistic, and if late normal tissue toxicity is independent of acute radiation-drug interaction, improved local control rates may be achieved. The combination of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil was tolerated very well in our patients with acceptable toxicity which is similar to the phase-II trial by the GOG. (14) In this study, an acute cutaneous reaction to chemoradiotherapy was the commonest adverse effect. Moist desquamation occurred in 20 patients, these side effects can be easily minimized with recent radiation techniques like 3-D RT and use of intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Beriwal et al. studied the use of IMRT with VC and reported that none of the patient had grade III acute toxicity

[19].

treatment failures occurred during the initial 2 years after primary therapy. During this period, patients with positive inguinal nodes relapsed early as compared to node negative. Thus, presence of positive nodes at presentation is a predictor of outcome for early relapse in patients with vulvar carcinoma

[8, 20]. Most failures in our study were locoregional which indicates that higher radiation doses which can be given safely with newer radiation techniques like three-dimensional RT and use of intensity modulated radiotherapy. Because of higher chances of locoregional failures examination of regional nodes should be part of follow-up for patients treated for carcinoma vulva. Beriwal et al. has shown that use of IMRT with vulvar carcinoma with minimal toxicity and reported 2 year survival 100%.

Small sample size is one of limitation but it has shown the prognostic significance of FIGO stage and nodal positivity. This is the study only from one center so it doesn’t represent the true incidence in our country. The short median follow up may be a limitation which is because of logistic issue. So we need more patients and longer median follow-up to draw any conclusion regarding outcome of this disease.

Conclusion

Because of higher local recurrence rates, groin examinations should be done carefully. Assessment of distant sites of failure should be included on routine follow-up. Majority of patients present in locally advanced stages so multidisciplinary approaches should be used to have better management options. The use of pre-operative chemoradiation and surgery should be explored as it seems to have better outcome compared to radical chemoradiation. Overall survival is quite comparable to the reported series.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publishing this case

series. The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contributions

IH: Concept and design of the study.

KUR: prepared the

draft article

UM: conducted the literature search and helped with draft.

AR: Drafting of the article and its review

MAI: literature search and

interpretation of results

KS: Acquisition of data

SU: Acquisition of data

AR: Acquisition of data

SAA: Analysis and interpretation of data

UM:

Edited the final manuscript and interpretation of data

AJ: Administrative,

technical and material support

SH: Supervised research.

Funding

None

Acknowledgement

None

References

[1].Sturgeon SR, Briton LA, Devesa SS, Kurman RJ. In situ and invasive vulvar cancer incidence trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 166:1482–5[Pubmed]

[2].Franklin EW, Weiser EB. Surgery for vulvar cancer. Surg Clin North Am 1990; 71(5):859.

[3].Creasman WT, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on early stage invasive vulvar carcinoma. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer. 1997; 80:505–13[Pubmed]

[4].Sekowski A, Majeed U, Interewicz B: HIV-related cancer of the vulva in young women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26(7):717-8[Pubmed]

[5].Majeed U, Sekowski A, Ooko F. Vulvar cancer in HIV-positive young females. S Afr Med J. 2006 Oct;96(10):1044

[Pubmed]

[6].De-Cherney AH, Goodwin TM, Nathan L, Laufer N: Vulval Cancer. Current diagnosis & treatment Obstetrics & Gynecology. 10 editions. McGraw-Hill; 2007, 822-7.

[7].Montana GS, Kang SK. Carcinoma of the vulva. In: Halperin EC, Parez CA, Bracdy LW, editors. Perez and Brady’s Principles and Practice of Radiation Oncology. 5th ed.London:Lippincott Williams and Wilkins;2008 pp 1692-1707.

[8].Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al. Assessment of current International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging of vulvar carcinoma relative to prognostic factors for survival (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study). Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:997-1003.

[9].Lin JY, DuBeshter B, Angel C, Dvoretsky PM. Morbidity and recurrence with modifications of radical vulvectomy and groin dissection. Gynecol Oncol 1992; 47:80-6.[Pubmed]

[10].Gould N, Kamelle S, Tillmanns T, et al. Predictors of complications after inguinal lymphadenectomy. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 82:329-32

[Pubmed]

[11].Landoni F, Maneo A, Zanetta G, et al. Concurrent preoperative chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C and radiotherapy (FUMIR) followed by limited surgery in locally advanced and recurrent vulvar carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1996; 61:321-7.

[12].Gerszten K, Selvaraj RN, Kelley J, Faul C. Preoperative chemoradiation for locally advanced carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 99:640-4.[Pubmed]

[13].Lupi G, Raspagliesi F, Zucali R, et al. Combined preoperative chemoradiotherapy followed by radical surgery in loc ally advanced vulvar carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer 1996; 77:1472-8.[Pubmed]

[14].Moore DH, Thomas GM, Montana GS, Saxer A, Gallup DG, Olt G. Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulvar cancer: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998; 42:79-85[Pubmed]

[15].Bafna UD, Devi UM, Naik KA, Hazra S, Sushma N, Babu N. Carcinoma of vulva: A retrospective review of 37 cases at a regional cencer center in South India. J Obstet Gynaecol 2004;24:403-7

[16].Sharma DN, Rath GK, Kumar S, Bhatla N, Julka PK, Sahai P. Treatment outcome of patients with carcinoma of vulva: Experience from a tertiary cancer center of India. J Can Research and Therapeut 2010;6:503-7

[Pubmed]

[17].Faul CM, Mirmov D, Huang Q, Gerszten K, Day R, Jones MW. Adjuvant radiation for vulvar carcinoma: Improved local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997; 38:381-9[Pubmed]

[18].Homseley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, Adcock L. Radiation therapy versus pelvic node dissection for carcinoma vulva with positive groin nodes. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68:733-40

[Pubmed]

[19].Beriwal S, Heron DE, Kim H, King G, Shogan J, Bahri S, et al. Intensity modulated radiotherapy for the treatment of vulvar carcinoma: A comparative dosimetric study with early clinical outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006; 64:1395-1400[Pubmed]

[20].Paladini D, Cross P, Lopes A, Monaghan JM. Prognostic significance of lymph node variables in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Cancer 1994; 74:2491-6

[Pubmed]